who can say if the thoughts you have in your mind as you read these words are the same thoughts i had in my mind as i typed them? we are different, you and i, and the qualia of our consciousnesses are as divergent as two stars at the ends of the universe.

and yet, whatever has been lost int translation in the long journey of my thoughts through the maze of civilization to your mind, i think you do understand me, and you think you do understand me. our minds managed to tough, if but briefly and imperfectly.

does the thought not make the universe seem just a bit kinder, a bit brighter, a bit warmer and more human?

we live for some miracles. (liu, preface, viii)

there was supposed to be an introduction here, but i scrapped it. the point was really that, sometimes, i get ahead of myself and want to write about a book when i’m halfway through it, so i’ll start planning the post, take the photographs, and come up with a partial draft … and, then, the draft will sit there for any number of reasons.

and, so, this is a post of disparate parts, kind of, at least disparate in that these are two books i wanted to write about but took longer to get to than i’d like. one book i’m still reading; the other i plowed through and loved, my brain shooting off in a million directions because there were so many things i wanted to talk about; but i suppose that is the problem with blog posts and reviews and etcetera, that there is only so much space we have, only so many things we can tackle.

so here are a few things.

a mama omelette is two eggs; a baby omelette is one. if i’m making an omelette on a weekday, i make a baby omelette, and, if it’s a sunday, i make a mama one because it’s the weekend, and weekends should contain acts of indulgence and self-care.

i wrote about how i make my omelettes before, but here are images that i was going to pair with ken liu’s the paper menagerie and other stories (saga press, 2016). the problem with that plan, though, is that i read short story collections much slower than i read novels because someone once said that you shouldn’t rush through a short story collection — you should read one and pause and let it sink in before moving onto the next.

given that (and the fact that i have, like, seven books going at any given time), who knows when i’ll actually finish the paper menagerie, so i figured i might as well say this here: liu’s collection is fucking fantastic. it’s so good and smart and aware, and it’s beautifully written and nuanced and so freaking creative, but in these wonderfully subtle ways that weave together realism with fantasy and sci-fi elements and present these alternate worlds and scenarios that make you think, what if, what if, what if.

i appreciate fiction like this, fiction that challenges boundaries and preconceptions of what can be done within genre, within subgroups, within kind-of-not-significant-not-in-the-ways-we-make-them-to-be classifications like ethnic backgrounds, social backgrounds, whatever backgrounds. you could go into the paper menagerie thinking, oh, sci-fi, or, oh, fantasy, or, oh, asian writer, and you’d be thrown off with every story, forced to reassess these definitions you’re taught to impose on certain people and things as ways of being.

also, that titular story, “the paper menagerie,” will just crush your heart into oblivion.

six years i lived like this. one day, an old woman who sold fish to me in the morning market pulled me aside.

“i know girls like you. how old are you now, sixteen? one day, the man who owns you will get drunk, and he’ll look at you and pull you to him and you can’t stop him. the wife will find out, and then you will think you really have gone to hell. you have to get out of this life. i know someone who can help.”

she told me about american men who wanted asian wives. if i can cook, clean, and take care of my american husband, he’ll give me a good life. it was the only hope i had. and that was how i got into the catalog with all those lies and met your father. it is not a very romantic story, but it is my story.

in the suburbs of connecticut, i was lonely. your father was kind and gentle with me, and i was very grateful to him. but no one understood me, and i understood nothing.

but then you were born! i was so happy when i looked into your face and saw shades of my mother, my father, and myself. i had lost my entire family, all of sigula, everything i ever knew and loved. but there you were, and your face was proof that they were real. i hadn’t made them up. (liu, “the paper menagerie,” 192)

i make a damn good omelette.

september 30th, the day i received the news of my adoptive brother’s death, i also received a brand-new couch from ikea. to clarify, i was the only one who happened to be physically present the day my roommate julie’s brand-new couch arrived at our shared studio apartment in manhattan. (cottrell, 7)

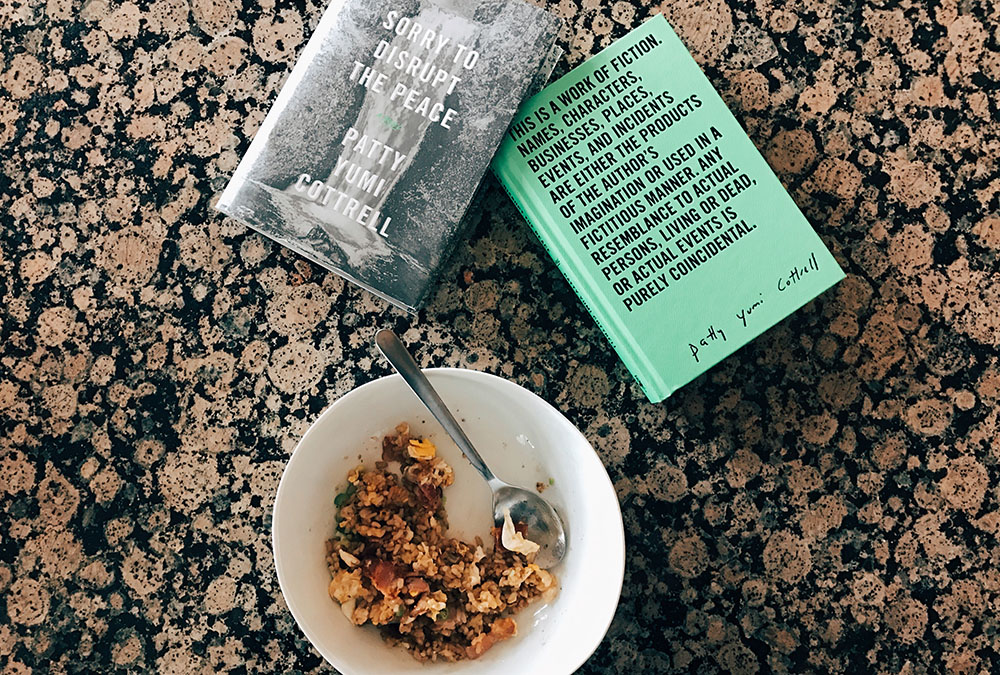

two weeks ago, i read patty yumi cottrell’s sorry to disrupt the peace (mcsweeney's, 2017), which i bought from the booksmith in san francisco. when i was in mexico, i was overwhelmed by this need to read her book and to read it now, so, once i landed in san francisco, i was on a quest to get to a bookstore and find it.

in the morning, i walked to tartine, picked up four croissants (yup) and a loaf of country bread, then walked over to dog eared books in the mission, but they didn’t have the cottrell, despite having a shelf dedicated to mcsweeney’s. the nice lady told me i should try 826 down the street; maybe they would have it; but it was too early in the morning and 826 was closed and i had to get on the road to LA sooner than later.

instead, i drove over to booksmith, up and down hills, which is something i loathe doing, driving on hills, while yelling demands at SF to tell me why it was so goddamn hilly. i’d wanted to go to the booksmith, anyway, though, because the booksmith took a stand against s&s during the milo what’s-his-face debacle, so i figured it’d be a good opportunity to go throw some money at them — and, no, of course, i didn’t call and ask if they had the cottrell in stock because i’m wild like that.

luckily, they had it, just one copy on the shelves. so i bought it. along with two cookbooks.

and i have no idea why i shared that whole story. i was damn proud of myself for driving in SF, though. i hate driving on hills; it gives me major anxiety.

it never occurred to me to intervene. i could be described as many things, but i was not an intervener, especially not when it came to my adoptive brother and his life, and perhaps the truth was i was afraid of intervening, because to intervene would mean to communicate with and confront my adoptive parents, people i hadn’t looked at in the face for years, perhaps because i was afraid of their faces and always had been. (cottrell, 155-6)

anyway, so, i got the cottrell, and then i read the cottrell, and i loved the cottrell.

sorry to disrupt the peace is narrated by helen, a woman in her 30s who goes back to her adoptive parents’ house in wisconsin after she learns that her adoptive brother has died by suicide. she seems kind of off, lost in her own way of thinking, not quite anchored to reality, and she goes back to her adoptive parents’ house, determined to investigate her adoptive brother’s death and learn why he killed himself.

her adoptive parents are surprised (not quite pleasantly) when she shows up, and she goes about doing her own thing while they plan the funeral, try to process their grief, receive visitors and guests and etcetera. in her head, helen thinks that she is contributing and helping out; she receives a cake and accepts flower deliveries; and, in an attempt to be thoughtful and make sure the flowers don’t die, she puts them in a bucket — except, later, of course, her parents discover the flowers, dead, in a bucket of bleach.

you could go about wondering whether helen is an unreliable narrator or not, and i have no idea if reviewers have hopped onto this debate with sorry to disrupt the peace because, truth be told, i don’t often read reviews. maybe it says more about me that, sometimes, i’ll read a book, and i’ll think, oh, i bet people are going to harp on this-and-this-and-this, and, often, that will usually have to do with unlikable female protagonists or unreliable female narrators or just things written by women because, yes, i do believe gender makes the difference here.

what do we expect from narrators, though? what makes a reliable narrator, anyway? narrators naturally only have their own truth to tell, and, when i say truth in this sense, i don’t mean truth in an “objective,” absolute sort of way; the point of the question is not to dredge up a debate on absolute versus relative truth. what we have as people, as individuals, is our own truth, and, as writers, that’s what we offer our readers in our characters — their authentic truth, whatever that looks like, how ever they define it.

that means truth in messy, complicated ways, truth that is sometimes so distorted by personal interpretation as to be considered madness or deceitfulness. maybe that translates into unreliable because we have this need to know things and to know true things, and it can be maddening to invest time and energy into a book told by a character who doesn’t seem to uphold her/his/their end of the unspoken bargain made between readers and narrators — that they are trustworthy, that they are taking you somewhere, that they aren’t just weird, random, unmoored beings spinning words on a page.

and helen is pretty weird, to put in one way. she has these ideas of what she can accomplish (deciphering the reason behind her adoptive brother’s suicide) and of who she is (sister reliability), and anyone might look at her and think that her grasp on reality is tenuous at best. it’s a testament, really, to cottrell’s writing that helen is so vibrant and alive, her voice popping off the page and drawing you in and pulling at your heart. in another writer’s hands, a narrator like helen might fall apart and ring so totally contrived as to be laughable. in cottrell’s hands, you get a narrator who’s vibrant and present and earnest, darkly funny, too, as she returns to her adoptive parents’ house and goes about doing her own thing, in her own head, as the people around her try to mourn.

thing number two! in an interview with the paris review, cottrell said:

a few years ago, i said i was writing an antimemoir. i was thinking of it as a response to people who suggested that i write a memoir, which i was never interested in doing. the further along i went, the less it became a preoccupation, though. the autobiographical details that overlap with the book — they're very emotional, i was writing from a place of emotion. but i wasn't hoping to create confusion between me and helen. if people want to read the details of my life into the events in helen's, that choice has nothing to do with me. that's the reader's response, which is private and subjective.

the question i kept asking myself was, why do people expect fiction to be autobiographical?

or, i suppose, more specifically, why do people except fiction written by certain people to be autobiographical?

if you go through a particular experience, if you’re a woman, if you identify as some “subset” of people, there’s this expectation almost that that one characteristic of yours is the thing that will define the entirety of you, the entire body of your work. everything you create is seen through this lens, like everything you create is some attempt to answer that question of who you are and why you are.

it’s like with suicide — if you die by suicide, then you and your life’s work will always be studied through the lens of your suicide. everything in your life will be rearranged to answer the question why.

while the question annoys me (how much of this is autobiographical?), it’s the underlying notion that irritates the hell out of me, these enforced narratives that are shoved upon us, that we’re expected to embody, narratives that are connected to the roles we’re expected to fill — and it’s irritating as hell because these enforced narratives, these ridiculous, stereotypical, privilege-laden expectations, are tied directly to silence and suppression.

for example, kids who are adopted are expected to be docile and grateful creatures, content if only for having been “rescued” and “blessed” with a “better” life, never mind that adoption is an act of trauma, of loss, of removal. similarly, they’re expected to stay silent and allow adoptive parents to speak for them and their experience and the “goodnesses” of adoption (all of which is amplified when you talk about transnational, transracial adoption) (and, oh god, we’re not getting into christians using children for self-aggrandizement).

rape victims are expected to be spotless, blameless, virginal, like a sexual history or clothing choices or alcohol consumed negates the violence they’ve endured. they’re expected to take it quietly, the act itself, the trauma, like rape is something you go through and move on from unscathed, like it’s nothing, just an act, just sex, just another night. women are told they “liked it,” that they, on some level, “asked for it,” and they’re blamed for trying to ruin the lives of men, men who have such potential, who will go on to illustrious futures and contribute wonderful things, so they shouldn’t be held back, not for something like this — such good men wouldn’t be rapists; what ugliness with which to smear them. in a bizarre twist, rape victims, too, are expected to be grateful, to be flattered that a man paid attention to them at all because what a privilege, so why can’t they just shut up when they liked it — they came, didn’t they?

anyone who’s marginalized is expected to stay quiet, to smile and speak nicely and educate the privileged in gentle, patient tones, while suffering discrimination, stereotyping, violence. we’re expected to be the tolerant ones, the accepting ones, like speaking up and saying, no, this is fucked up; this is wrong, make us hypocrites for rejecting the niceties and refusing to play by the stupid rules that continue to exploit us and appropriate us while pretending that we don’t exist.

and we all know this because, when we deviate, when we speak up, we are met with violence.

when [my adoptive father] played mozart or schubert the house filled up with white male european culture. we were expected to worship it, which we did for a while, but once i went to college, i stopped. there is a world and history of nonwhite culture, i wrote to them once in a furious letter. and you kept us in the dark our entire childhood! the two white people raised their asian children to think asian art was decorative: oriental rugs and vases! jade elephants! enamel chopsticks! (cottrell, 99)

to get from A to be B in more logical, clear terms, though, maybe it should be said that you wouldn’t expect a story to be autobiographical unless, on some level, that’s what you believe a person to be. maybe it’s a jump to go from a question that seems so innocuous (is this autobiographical?), but maybe sometimes writers are people, too, and we come from complex backgrounds that make us recognize the systemic -ism that allows the privilege of the pretense of innocence.

it’s why people of color get so pissed off when they get asked the where-are-you-from? question. on the surface, it seems like a harmless question, and maybe (who knows) the asker of the question does come from a place of genuine curiosity.

however, there’s so much [internalized] racism that lies beneath, so much prejudice and stereotyping, like the kind that might make someone speak in slower, exaggerated, louder english to an asian person, and it’s the kind that enforces the Other. it’s the kind that says that "you are from over there, and i am from here, and we should be placed apart from each other because we’re different.” it’s the kind that fetishizes an entire group of women by rendering them exotic and, thus, reducing them to the erotic, refusing to see them as people with brains and feelings and ambitions and histories and individual personalities. it’s the kind that makes violence against women so easy because it’s easy to justify, dismiss, ignore violence against a “lower” group of people.

and it’s easy to forget: violence begins from something as small as a seemingly innocuous question. the cycle of harm begins with something supposedly innocent.

all it takes is seeing someone as Other than you.

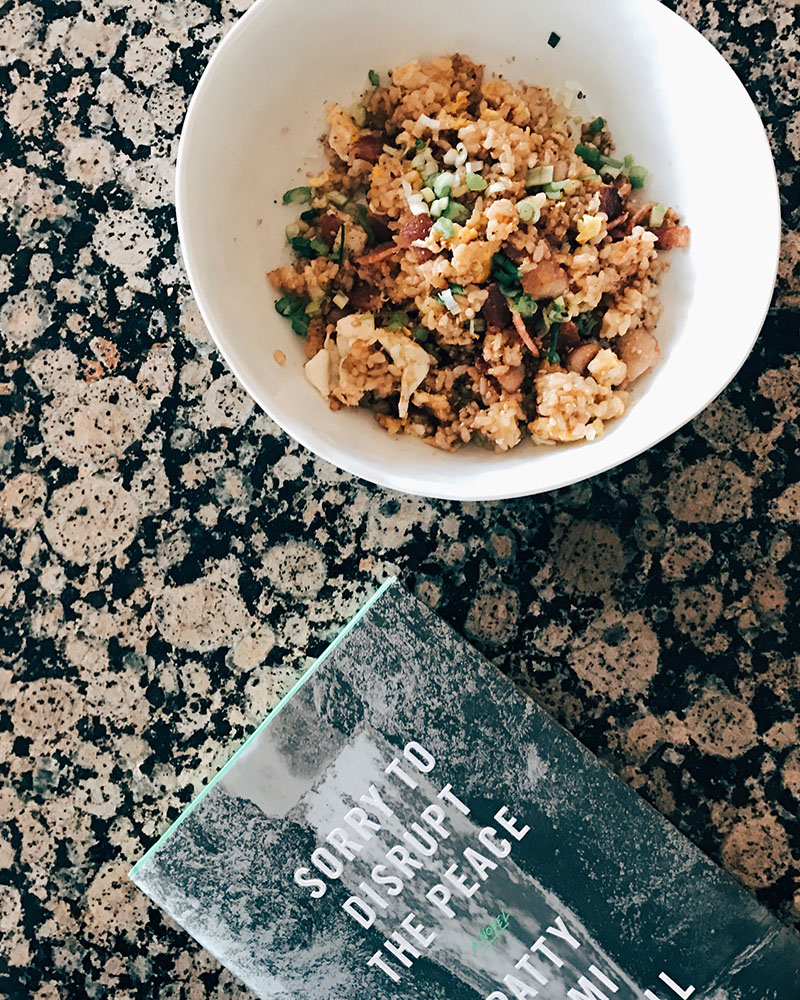

i cook the most basic things, but i’m all right with that — i like basic shit, especially when it’s done well, though was that me complimenting myself and patting myself on the back?

bacon fried rice is stupid easy. chop up some bacon (my favorite bacon is the applewood smoked bacon from trader joe’s), and fry it up. add some rice, and mix it up. pour a little sesame oil to the side, and crack an egg in it. mix the egg into the rice + bacon mixture. season with some soy sauce. garnish with a whole lot of toasted sesame seeds. add some chopped scallions if you’re feeling fancy.

eat. don’t forget the sri racha.