a few years ago, i made a conscious decision to read only from authors of color, and that scope has narrowed further over time to focus on asian/asian diasporic authors, mostly korean. 2023 was spent mostly reading for research for my book, which was incredibly insightful and informative (unsurprisingly) and has helped provide more context for my casual reading, especially of korean literature-in-translation.

two (more generalized, less specialized) books that stood out to me were hannah michell’s EXCAVATIONS (one world, 2023) and vincent cha and ramon pacheco pardo’s KOREA: A NEW HISTORY OF SOUTH AND NORTH (yale university press, 2023). the former is a novel set in mid-1990s korea around the collapse of a fictional department store (which was based on the actual collapse of the sampoong department store in 1995), and the latter a book of nonfiction by two diplomats to korea, focusing on the twentieth century and providing inside political observations and insight into the ever-present question of reunification. the two books pair very well, and i recommend reading them together.

the twentieth century was a tumultuous time for korea, starting with her occupation by imperial japan, which ended when the united states dropped atomic bombs on hiroshima and nagasaki and brought an end to world war ii. (in an incredibly gross display of tone deaf imperialist arrogance, the united states declined to attend the peace ceremony in nagasaki this year — the united states, the only country that has dropped atomic bombs, as it currently supports the genocide of palestinians and maintains military bases around the globe.) the united states and former soviet union then stepped in to divide the korean peninsula at an arbitrary point (literally — the white soldier who split korea in two at the thirty-eighth parallel knew nothing about korea and basically just pointed at a line on a map), which then led to the korean war, the first “hot” conflict of the cold war, which led to the decimation of the korean peninsula and the slaughter of korean civilians by the united states, until a ceasefire was signed between north korea, china, and the united states in 195#. the korean peninsula remains in an active state of war, and the united states maintains its interest in the region with military bases that mete out its usual murderous and environmental harm. truly, the U.S. military industrial complex is a global scourge.

since the 1950s, korea has moved in two directions — the north under dictatorship and with closed borders, the south taking on an unofficial policy of americanness-as-aspirational that took the famine-ridden, poverty-stricken post-war country rapidly through development, military dictatorships and coups protested by demos led by university students and factory workers, its first real democratic elections in the 1980s, an introduction to the global stage via the 1988 summer olympics, financial failure in the IMF crisis in the late 1990s, to a massive success as the twelfth-largest economy in the world by the 2010s. korea today wields immense soft power through its cultural output, and korean brands are no longer laughed at but desired around the world.

today, korea is cool.

a few weeks ago, i read monika kim’s THE EYES ARE THE BEST PART (erewhon, 2024), a debut novel by a korean american author set in los angeles. the novel is told from the perspective of a korean american college student (with a younger sister) whose father leaves their family for his mistress, causing their mother to fall apart as she waits for him. eventually, their mother meets an older white dude and brings him home, and he’s as we, the reader, would expect of a toxic white male — sleezy, racist, entitled, deceitful, unfaithful. this portrayal gets under my skin because of how realistic kim is, leaning into the trope, sure, but not playing into hyperbole, but, as i read the novel, i found myself thinking more and more about how trope-y the book is and how it doesn’t really extend past that.

i believe that books should be in dialogue with other books and with culture at-large and that authors should be aware of their place in the greater ecosystem of writing. this was one of my key issues with r.f. kuang’s YELLOWFACE (william morrow, 2023) — setting aside serious issues with her lack of craft and weak writing, kuang tends to write books that are reactive to a specific “issue” she has chosen as her Theme for the current book at-hand. in THE POPPY WAR (harper voyager, 2018) it was east asian history and the scourge of white [missionary] imperialism. in BABEL (harper voyager, 2022), it was white imperialism and empire. in YELLOWFACE, kuang took on racism in publishing, except this book particularly ended up really laying bare her weaknesses as a writer, partly, in my opinion, because racism and publishing have both been in the discourse for many, many years. all YELLOWFACE does is regurgitate the same old shit people of color in the literary community have been yelling about long past the point our metaphorical throats are hoarse, though kuang does seem to braid in personal grievances she seems to have (i don’t believe at all that athena isn’t her).

kuang is a fast writer, which could be a strength in some ways but ends up being her fatal weakness as she never seems to have invested the time or energy to develop her craft. she’s dabbled in different genres, like fantasy and magic realism, but, because her writing is so reactive and fueled, it seems, by impulse and reliant upon inspiration, she never actually gives herself the time to dig into a genre and become a better writer, instead scaffolding skeletons of her worlds out of matchsticks for the purpose of getting a book out but failing to build them out in any meaningful way. THE POPPY WAR trilogy bypassed a lot of criticism, in my opinion, because the books are very propulsive and superficially enjoyable, but BABEL showed more holes (why are the silver bars magic?!), while YELLOWFACE exposed all its frayed edges — unless kuang slows down and actually invests the time and care to develop her craft, she’ll never pass this limitation.

my point, though, was — YELLOWFACE is about racism in publishing, sure, but it’s a bad faith book, in my opinion, because there’s a particular ego driving the center of the book instead of a more expansive perspective. fiction is weird in that it can (and should) have some kind of point-of-view, especially if there is a topic the author is trying to address, but there’s a fine line between that and moralizing, so i understand that there is a tricky balance to this. regardless, i think it’s fair to have a basic expectation that any writer should sit down with her craft.

that was a longer tangent than i initially intended, but what i wanted to say is that kim’s THE EYES ARE THE BEST PART has a similar problem when it comes to tropes and perspective. by this point in the zeitgeist, we know about the toxic white male. we know about him in the context of asian women, yellow fever, racism and misogyny. we know about his gross entitlement. we live and exist in the world.

kim doesn’t bring anything new to this discourse — her novel is basically about how the presence of two white men throws the korean american narrator’s life haywire. she’s already struggling with the effects of her father leaving, and now here are two white men — one, her mother’s new boyfriend, the other, a classmate in her philosophy courses at college — against whom her life ends up being defined. sure, the novel narratively tracks the arc of her getting rid of these two toxic figures in her life and allegedly regaining her agency, but, again, we’ve seen this story before.

i admit that part of me was already disappointed because i was led to think that THE EYES ARE THE BEST PART was literary horror, but it isn’t, not really. there are some weird, horror-esque elements, sure, and there’s bloody violence involved, but i think this muddled lack-of-something is another effect of leaning into a trope instead of developing a point-of-view. the novel isn’t satirical, either, because satire requires a deeper commentary, in this case, about being a korean american woman in this world. kim simply presents her story as is, giving nothing beyond the surface level, and, as i closed the book and looked for my next read, i realized how tired i am of the specter of whiteness, of how we as korean americans cannot often seem to help but define ourselves against whiteness — and that is why all i have wanted to read this summer has been korean literature-in-translation.

americanness-as-aspirational has been built into korean culture since the postwar, intentionally so in several ways when korea was a poor, famine-ridden country with nothing, so it isn’t necessarily totally true to say that there is an absence of whiteness in korean literature. there’s a lot more chatter these days about decolonizing cultures of color from imperialism, but i think there are massive limits to that given how much whiteness (often via capitalism) has simply been built into the global world as desirable and unavoidable.

in such a world, i’m generally done with the tropes that have been deemed by the white establishment as “acceptable” for asian americans. we’re supposed to be ashamed of our culture, our food, our immigrant parents who can’t speak english without an accent. we’re supposed to have gone on some journey of rediscovery of our ethnic backgrounds now that’s it’s cool to be certain kinds of asian, while still accepting our role as the model minority. we’re supposed to be embarrassed if we can’t speak our ethnic languages, like many of us weren’t taught from young ages to eschew those very languages. there’s so little room for joy for asian americans in the western mainstream, just a lot of self-loathing and shame, and so little space for pride in who we are and where we come from, and i’m honestly over it.

whenever i talk about this, though, i feel the need to add the disclaimer that i know i got lucky in many ways, growing up bilingual and bicultural because my appa was stubborn and wanted his kids to know korean (though this only succeeded with me) and because i happened to fall into k-pop when i fell into pop culture in middle school. i was raised in suburban los angeles and attended schools where asians were technically a minority overall but the majority in honors/AP classes, and i spent my life at a korean church. the two facts together meant that my social circle was entirely asian; the only white person i interacted with regularly (other than my teachers at school) until i moved to brooklyn for law school was my flute teacher.

that doesn’t mean i have a perfect history with koreanness. i was disconnected from my culture starting in high school with body shaming, but even that was rooted in koreanness because i was held to korean beauty standards. that meant that the community whose approval and acceptance i wanted was korean, that the standards i held myself to, beauty or otherwise, were korean, that, to this day, the way i see myself primarily is as a korean. in general, despite the tremendous harm my own community and people meted upon me, i grew up fiercely proud of being korean, and you still can’t take that away from me today. i wish we could see more of this reflected in our stories instead of the internalized racism that continues to keep us chained to whiteness, whether we see that whiteness as toxic or not. i’m not saying that, partly as asian americans, we should deny that we live in a white world and pretend that racism, microaggressions, and white toxicity don’t exist and impact our daily existence, but it is one thing to acknowledge reality and a whole other thing to choose to perpetuate the narrative white media has decided to permit to us. we are so much more interesting and complex and fun than that.

and, so, all i’ve wanted to read this summer has been korean literature-in-translation, with some japanese lit-in-translation thrown in there. part of this is also tonal — i’m working on my second book, and there’s a certain tone i’m trying to pull through the prose that is inspired from what you find in literature specifically translated from korean and japanese. i struggle, still, to explain this adequately, and it isn’t a shortcoming of translation but a natural byproduct of flipping a language from one to another, especially two languages as different as korean and english. korean and english have different grammatical structures. korean is not nearly as dependent on pronouns or gender as english is. korean also allows for more room for long, poetic rambling, and korean also has more words for more concepts and feelings than exist in english.

so, here’s a bit about translated books i’ve been reading.

my favorite book this year has been cho yeeun’s NEW SEOUL PARK JELLY MASSACRE, translated by yewon jung (honford press, 2024), and i am obsessed with it. in my head, i still keep calling it new seoul jelly park, and i don’t really want to give away many details because it is a strange book, which, to me, is delightful. you just have to embrace the weird and lean into the fact that you won’t get clear answers, but there’s a lot of heart in this book, questions about love, family, and loneliness.

another favorite thus far has been kang hwagil’s ANOTHER PERSON, translated by clare richards (pushkin press, 2023) — and this also makes me ask why translators are not just, by default, being listed on the covers of their books, here in the year 2024. ANOTHER PERSON is enraging — the novel hops around different characters, but it centers on jina, a twenty-something woman who has had to leave her job and retreat from society after she filed a claim against her ex-boyfriend (ex-coworker) for domestic violence. she’s been harassed at work and on the internet, even though he’s the one who physically assaulted her, and, as she hides away in her apartment, she comes across a tweet that sets off a particular memory of her college years and sends her down to her college town.

ANOTHER PERSON ultimately pulls back to tell us the story of three women who went to the same college and experienced sexual assault, each in different ways. what i particularly appreciated about the novel is that kang refuses to let the reader look away, not from the violence or from the ways men write off and dismiss violence against women (and, most of the time, rationalize it by blaming the victim) or, even, most uniquely and importantly, from how internalized misogyny affects and harms women. one of the core problems with the misogynistic patriarchal world we live in, whether in the U.S. or in korea, is double-fold — that men are encouraged to be violent to get what they believe they are entitled to (the bodies of women) and that women are made to accept and internalize that abusive misogyny.

this is another novel i think has a great nonfiction pairing — hawon jung’s FLOWERS OF FIRE (benbella books, 2023), a nonfiction book that looks at the #metoo movement in korea and the gender, in general, in the last five to ten years. the chapters are super short, and jung’s writing is incredibly readable, imparting a lot of information in a digestible way, so the book goes fairly quickly. i highly recommend both.

one specific thing that has been delighting me about korean and japanese literature is structure. korean and japanese authors play with structure and form in really creative, thoughtful ways that we just don’t see in english-language fiction. like, hiroki kawakami’s UNDER THE EYE OF THE BIG BIRD, translated by asa yoneda (soft skull, 2024), which is another book i won’t say much about because i think you just need to read it — the way the stories unfold is incredible.

kwon yeo-sun’s LEMON, translated by janet hong (other press, 2021), also plays with structure and narration, in this case to discuss the murder of a girl, hae-on, in high school. we never hear from hae-on as it has now been years since her unsolved murder, and, instead, the novel is told from three women who each knew hae-on in some way. this is another of those books that doesn’t have clear answers; it’s about a murder, yes; but it isn’t a murder mystery, which i think is totally clear from the start.

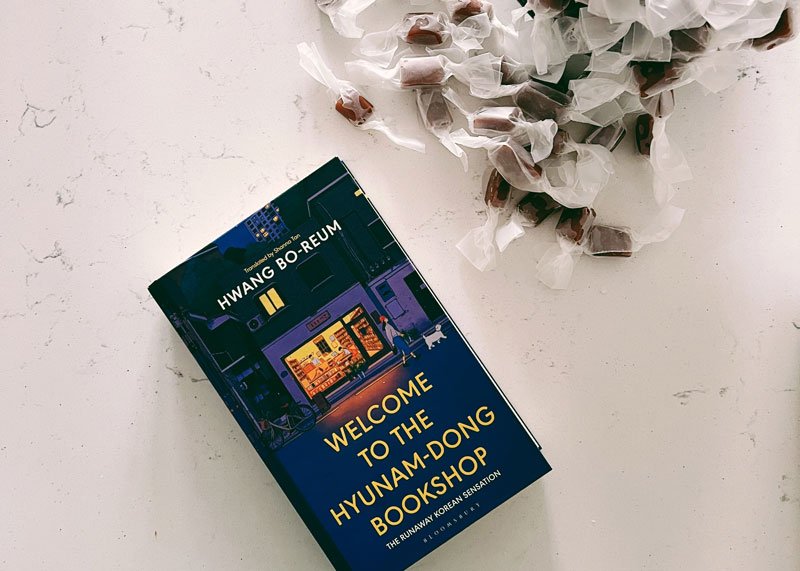

in my reading, i did also dip my toe into the world of cozy fiction, which is really not my thing at all. i was, however, very pleasantly surprised by hwang boreum’s WELCOME TO THE HYUNAM-DONG BOOKSHOP, translated by shanna tan (bloomsbury, 2024) — i read this at the end of last year, during a period of my life when i was feeling blue, and i found the book to be very warm, thoughtful, wise, a slice-of-life novel about a bookstore in a quiet neighborhood in seoul. HYUNAM-DONG asks questions of being a human in the rat race, and some of it is unique to life in hell joseon, but i think there’s universal wisdom to take about the value in slowing down and choosing to abstain from what society tells us is important, especially when those arbitrary markers of success suck us dry.

i liked HYUNAM-DONG so much, i also picked up lee miye’s THE DALLERGUT DREAM DEPARTMENT STORE, translated by sandy joosun lee (hanover square press, 2024). (i also wanted it because i love this UK cover; it makes me think of IU.) the world in DALLERGUT is lovely, but the novel ultimately fell very flat for me because all the characters are, well, flat, each clearly meant to play a specific part in the world, instead of being a three-dimensional, developed character. it didn’t surprise me to learn that lee is an engineer, which maybe is an unfair stereotypical statement for me to make, but i was very much impressed by the mechanisms behind the world in DALLERGUT. i just wish lee had spent as much time and care in fleshing out her characters and lingering more in the day-to-day — it was clear that lee wanted dallergut (the owner of the department store) to be this quirky, wise character and that the dreams she focuses on are meant to impart wisdom, but, because the book zips along too quickly and superficially, these potential moments of insight and poignanch feel heavy-handed instead. i do wish someone would make a drama out of DALLERGUT, though, because, again, the world itself is vibrant and colorful, and i think it would be really fun to watch.

asako yuzuki’s BUTTER, translated by polly barton (ecco, 2024), and yoko ogawa’s MINA’S MATCHBOX, translated by stephen b. snyder (pantheon, 2024), were both quiet books, and i particularly enjoyed BUTTER, which ostensibly is the story of a journalist trying to get a murderess to talk. the murderess is in jail, and she’s all about food and luxury, and she sends the journalist essentially on missions to eat something and experience it in a specific way, but this isn’t tantalizing or sensational. BUTTER, instead, is a thoughtful book about loneliness, friendship, and, yes, the role food plays in our lives.

two other quiet books i enjoyed were by kim hye-jin, CONCERNING MY DAUGHTER (restless books, 2022) and COUNSEL CULTURE (restless books, 2024), both translated by jamie chang. DAUGHTER, particularly, got to me — it’s narrated by an ajumma in her sixties who works at a senior care facility and has her life upended when her thirty-something-year-old daughter moves back in … with her female partner. the daughter is an adjunct professor who also attends protests demanding a more equal society for queer people, and the mother doesn’t understand any of this. the book isn’t an easy one to read; kim doesn’t try to make the mother a sympathetic character; but neither is she unfair. the mother is a product of her times, a woman who struggled to raise her daughter alone after her husband passed away, who grew up in very heteronormative korea, who just wants her daughter to live a stable, safe life, and there is deep poignancy and resonance in her struggle to understand her daughter. i appreciated kim’s realistic portrayal of this ajumma’s journey — she doesn’t reach the ending we might hope for, but CONCERNING MY DAUGHTER is a great depiction of how the journey is what matters, that we at least make the effort to see beyond the narrow scopes of our upbringing.

i did also quite like COUNSEL CULTURE, which is about a therapist who says something thoughtlessly about an actor on a TV program then is blamed, months later, for his death by suicide. she ends up divorced and jobless and gets drawn into a mission to trap an injured stray cat and find him a home, collaborating with a loneliness grade school student with divorced parents. the book is a thoughtful look at perception and the ways we have all cast ourselves as commentators thanks to the internet.

to shift gears, kazuki kaneshiro’s GO, translated by takami nieda (amazon crossing, 2018), is an example of when exposition works in a novel. kaneshiro is a zainichi korean, and his YA novel builds off the story of a zainichi korean kid developing a romance with his japanese classmate to explore the complications of being a zainichi korean, which requires a fair amount of history background and explained social context — but kaneshiro manages to provide all this without feeling pedantic or taking us out of the story, which i think is a feat. i also enjoyed park soyoung’s SNOW GLOBE, translated by joungmin lee comfort (delacorte press, 2024), which takes place in a frozen dystopia and was a fun read that has quite a few twists that keep it from being predictable.

finally, paek nom-nyong’s FRIEND, translated by immanuel kim (columbia university press, 2020), was wildly informative, not so much because of anything it says explicitly about life in north korea but because of how much propaganda is implicitly in it. paek is a north korean author — like, he isn’t a refugee, and he hasn’t left north korea — he writes in the north. FRIEND was published in the north in 1988, then published in the south in 1992, so this isn’t a novel that wasn’t smuggled out.

the novel is incredibly readable despite feeling dated, and it follows a judge who has to decide upon an application for divorce that has landed on his desk. this isn’t unique in and of itself; people get divorced. the wife, in this case, is a singer, the husband a lathe operator at a factory. the wife also started as a factory worker, which is how they met, before she became a singer after they married, becoming something of a celebrity. they have a young son. she thinks they are not well-matched — she has grown and developed through their marriage, but her husband seems content as a mere lathe operator, ignoring her pleas to get a degree in engineering and absorbing her contempt as his attempted inventions amount to nothing.

the novel is meandering as the judge meets the couple and interacts with other couples, reflecting on those marriages as well as his own, and we drift along people’s memories as they look back on the early years of their marriages and think about the challenges they have faced along the way. it’s a pretty poignant, thoughtful book, obviously absent the tropes we see in the west when it comes to north korea, though it’s hard to say how much we should take from FRIEND about life in the north. i mean, there’s no way for us to know, and we do also have to consider that the book was published in north korea, maybe not a state-sanctioned novel but one that clearly was permitted publication, but, as i read this book, i hoped that there was some truth to it — and i did believe that there was some truth to the world paek presents because north korea is an actual place with actual people, and, where there are people, even in isolated, repressive regimes, there is still love.