it’s hard to make a bad skillet of cornbread. just don’t add sugar. (120)

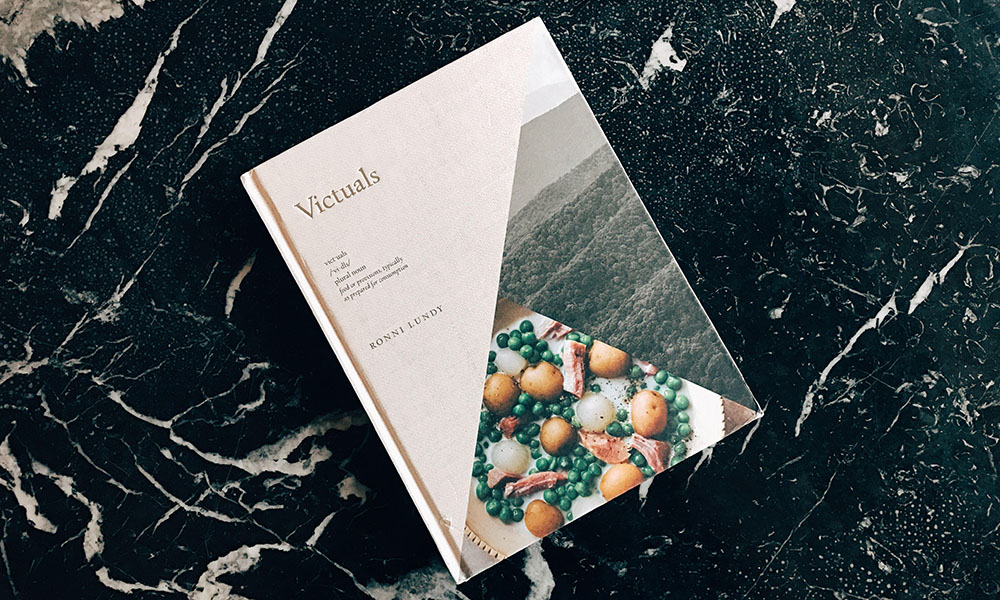

it’d be simple to call victuals (clarkson potter, 2016) a cookbook because, yes, there are recipes, and, yes, there are instructions as to how to cook said recipes, but i love the subtitle and find it more apt a descriptor: “an appalachian journey, with recipes.”

ronni lundy, the writer, grew up in appalachia, and victuals is a tribute to the “present-day people and places across the southern appalachain mountains” (16). lundy set off on an epic road trip to write the book, traveling over four thousand miles, driving through and around kentucky, west virigina, southern ohio, northern georgia, tennessee, virginia, and north carolina to bring us all these stories — stories from her own childhood and youth, from chefs and food people who have roots in appalachia, from people who live and work in the region, dedicated to cooking its food and preserving its history and traditions.

and, of course, there are recipes and beautiful — seriously, exceptionally beautiful — photography.

victuals hits at that intersection that i absolutely love — literary writing/journalism and food and culture. the chapters open with long-form pieces that focus on different components important to appalachian food and culture, and they’re rich with history and also steeped in the present. one of the things i appreciated most is how lundy doesn’t shy away from the uglier aspects of history; she readily acknowledges the role of slaves and indentured servants and doesn’t try to gloss over it or pretend it didn’t exist (79-81).

she also brings in the present, highlights the work that people are doing to preserve the food of appalachia as well as to reclaim land that has been completely stripped by big coal. she does all this without getting preachy, by focusing on the stories of the people doing the work on the ground, by helping us get to know them, who they are, why they’re doing the work they do. fundamentally, lundy understands that people, that stories, are a crucial part of any culture, including food, just as she understands that food does not exist in a void — these practices, these flavors and products and dishes all have origins somewhere.

how does victuals fit into this series, though? this series that is meant to highlight books by authors who are immigrants, POC, LGBTQ, women, etcetera? isn’t ronni lundy a white, american-born, american-bred woman?

yes, she is, and, yes, that is the underlying premise of this series, but the greater purpose behind this is to open up the world a little, whether for me or for someone out there who might have chanced upon this page, and victuals personally challenged me a lot.

last december, i posted this quote from becky chambers’ a closed and common circuit (hodder and stoughton, 2016):

’and here, AIs are just … tools. they’re the things that make travel pods go. they’re what answer your questions at the library. they’re what greet you at hotels and shuttle ports when you’re travelling. i’ve never thought of them as anything but that.

‘okay,’ sidra said. none of that was an out-of-the-ordinary sentiment, but it itched all the same.

‘but then you … you came into my shop. you wanted ink.i’ve thought about what you said before you left. you came to me, you said, because you didn’t fit within your body. and that … that is something more than a tool would say. and when you said it, you looked … angry. upset. i hurt you, didn’t i?’

‘yes,’ sidra said.

tak rocked her head in guilty acknowledgement. ‘you get hurt. you read essays and watch vids. i’m sure there are huge differences between you and me, but i mean … there are huge differences between me and a harmagian. we’re all different. i’ve been doing a lot of thinking since you left, and a lot of reading, and —‘ she exhaled again, short and frustrated. ‘what i’m trying to say is i — i think maybe i underestimated you. i misunderstood, at least.’

[…]

sidra processed, processed, processed. […] ‘this … re-evaluation of yours. does it extend to other AIs? or do you merely see me differently because i’m in a body?’

tak exhaled. ‘we’re being honest here, right?’

‘i can’t be anything but.’

‘okay, well — wait, seriously?’

‘seriously.’

‘right. okay. i guess i have to be honest too, then, if we’re gonna keep this fair.’ tak knitted her long silver fingers together and stared at them. ‘i’m not sure i would’ve gone down this road if you weren’t in a body, no. i … don’t think it would’ve occurred to me to think differently.’

sidra nodded. ‘i understand. it bothers me, but i do understand.’

‘yeah. it kind of bothers me, too. i’m not sure i like what any of this says about me.’ (chambers, 189-90)

this passage has sat with me since, and it’s a quote i kept thinking about as i read victuals. i’m just as guilty as anyone else of living in a bubble, having preconceptions of groups of people, and not wanting to look myself in the mirror because i know i won’t like what i see.

i readily admit that, when i think of the south and middle america, which are geographical terms i use very loosely to mean anywhere south of DC and west of philadelphia, my immediate reaction is to raise my guard. i automatically get wary and suspicious, and i start feeling uncomfortable. this isn’t a reaction limited to the south and middle america, though; it’s also my instinctual reaction when i think of christians, suburban white americans in general, korean-koreans.

victuals made me examine that part of myself, made me continue asking myself about these biases of mine. i thought a lot about this as i was driving across the country last month, as i made my way through the south, and i’d like to say that a lot of it has to do with being a woman of color and being queer and having faced discrimination simply for being who i am.

while i won’t say that all my apprehensions are totally unwarranted given that, yes, this country did put the cheeto administration in place, knowing it to be racist, misogynistic, and anti-LGBTQ, i don’t think it’s fair to use my queer WOC-ness as an excuse for my own biases, and it goes without saying that i don’t like this part of myself. i don’t like that i’ll let my fear color my perception of people, of places.

at the same time, though, knowing this, i refuse to let my fear define my perception of people, of places, and neither will i let it stop me from going into spaces that make me uncomfortable and let them show me how wrong i’ve been. sometimes, though, of course that’s easier said than done, partly because fear is fear and partly because it’s never a nice feeling to come face-to-face with my own prejudices and ugliness. i mean, no one enjoys that; no one wants to be called a racist or a bigot or a misogynist; but this is why toni morrison said that, to her, goodness is more interesting than evil — it takes work to be good. it’s a struggle to be good. as much as hatred and bigotry are learned things, we also must learn to be good, to be better people, and that, oftentimes, hurts.

i feel like, post-election, there’s been a fair amount of criticism directed at liberals, kind of like a “ha, fuck you! you in your liberal bubbles, totally clueless about the rest of the world! we showed you!” there’s also been a call to empathy, that liberals should be reaching out to conservatives — or maybe that’s making a much too clear-cut distinction, like it’s solely a liberals vs. conservatives thing or like it’s solely geographical. i don’t know.

regardless, there’s been a call to liberals to be more empathetic, to try to understand where cheeto voters came from, what might have compelled them to vote that way, how the rest of the country outside of our liberal cities is faring. a small part of me thinks, well, yes, maybe we should try to understand, in the way that i think we generally need to keep our minds and hearts open, but the other, greater part of me thinks that’s a pretty piss-poor attempt to rationalize racism, misogyny, and bigotry, to reinforce the continued straight white male-centered power structure.

here’s the thing: empathy is a two-way street. you don’t get to call for empathy and understanding without first extending it to someone else, and this whole fucking country could stand to tap into more empathy and understanding. republicans could stand to tap into their basic humanity and try to see women as independent, sentient, thinking human beings deserving of equal rights and the legal right to make decisions about their own bodies. christians could stand to tap into love for LGBTQ people, muslims, non-christians, instead of crying about religious freedom so they can continue to discriminate against people at will. queer POC like myself could venture out of our bubbles and try to see the america outside our cities.

that’s the thing, though — you can’t expect just one group to carry all the weight of being empathetic and open-minded. it doesn’t work that way. it’s not fair to place that just on liberals, like it’s necessary for us to be open-minded and accepting of people and ideologies that try to do us harm and take away our rights and treat us like second-class people, when those people and ideologies do nothing to try to see outside their narrow bubbles. it takes both sides to bring about change and growth, just like it takes at least two people to have a conversation.

and, you know, this is something i love about food, its ability to bring people together and create a space where maybe people can put aside their differences and just enjoy a meal. it’s not to say that food has this magical superpower or that this is always what happens — people fight plenty over dinner tables — but, when i think of food, i do think of that, its giving, generous nature that invites people in and agrees that, no matter where we come from, who we are, we all eat, we all taste, we all need and want and hunger. fundamentally, despite our surface variations, we are not all that different from each other.

one afternoon she [amelia kirby] looked up to see seated at adjacent bar stools an openly gay local artist and one of the staunchest conservative strip miners in town. “they were each just here [at summit city] to grab lunch, but they were sitting there and you know how we are in the mountains, we like to be friendly. so they started to talk, and not just talk, but it turned out to be an hour-long conversation in which they exchanged ideas civilly, even though they each were coming from different perspectives. and they left, laughing pretty easy, and i thought, ‘wow. it’s working!’” (116)

in short, bill [best] teaches that american culture has evolved to largely value the acquisition of things: cars, tech devices, supper from the latest chef to make headlines. appalachian culture instead places a higher value on connections. beans are a perfect example of that as we value them not only for taste and nutrition, but also for less tangible reasons. we pass seeds from generation to generation, sharing their names and stories to connect us to our origins. we plant our preferred pole beans in the corn so the former may use the latter’s stalks to twine up, a connection of crops. the bean plant replenishes nitrogen sapped from the soil, connecting us to the earth. we see the thick strings down the sides of the beans we prefer not as a nuisance, but as an opportunity to gather on the porch willing hands of all ages, the older women teaching children how to pull the zipper gently down one side, then the other. as we work, we share gossip and memories connecting us to our family, our community, and our history. bill notes that being intangible, such treasures of a culture of connection are virtually invisible to the citizens of a culture of acquisition and so mountain culture gets cast, at best, as quaint and anachronistic; at worst, ridiculous or perverse. bill urges us to look past such assumptions, to dig deeper for the truth. he also grows some mean beans. (141)

“aspirational eating” is a term used in the study of foodways that, in its most simplified explanation, means that we eat the foods of those we aspire to be. the theory suggests that the movement that began in the region in the mid-20th century toward convenience foods and commercial products, toward pop-tarts for breakfast instead of homemade biscuits and mamaw’s jelly, is not simply about availability, convenience, inexpensive price, or taste preference, but is also largely fueled because people from this part of the country, who so often are portrayed as “other,” aspire to be instead “the same.” like those they’ve seen selling foods on billboards and tv.

[…]

i thought about my mother, who i remember working tirelessly most days of her life, cooking, cleaning, washing clothes and hanging them on the line, washing pots and pans in an old porcelain sink. what did grocery canned goods mean to her? she relished the home-canned goods that we were gifted, adjusted the store-bought ones to suit her rigorous standards of taste. i thought that she loved her aunt’s jams as much for the memory of place and people they evoked. but what meaning might those commercial jams and vegetables have also held? did those grocery jars and tins represent a different life? perhaps an easier one; perhaps one she desired?

was that aspirational eating? (211-3)