i can package a certain story as a dream and tell it that way. i can disguise my childhood, and as i disguise it i can make allusions, and as i reveal details about the allusions, i can make them appear fictitious, and in this way, i can deceive you all. but you won’t be deceived. (han, 148)

i always hated writing introductions — introductions and conclusions. in college, i’d always start with the stuff in the middle, oftentimes without even establishing a thesis first because the middle had to be worked through for me to discover what my thesis even was. once all that was written and done and good, i’d write the conclusion. then i’d write the introduction. none of this has changed.

coming back to korean literature-in-translation after some time away is one kind of homecoming, and i love how we’re getting more and more of it here in the west. i love that i’ve been reading more and more of it because, a few years ago, this was a wish of mine: to read more korean literature, to be able to know more of it, to be able to share more of it.

and i am so happy to be able to share more of it.

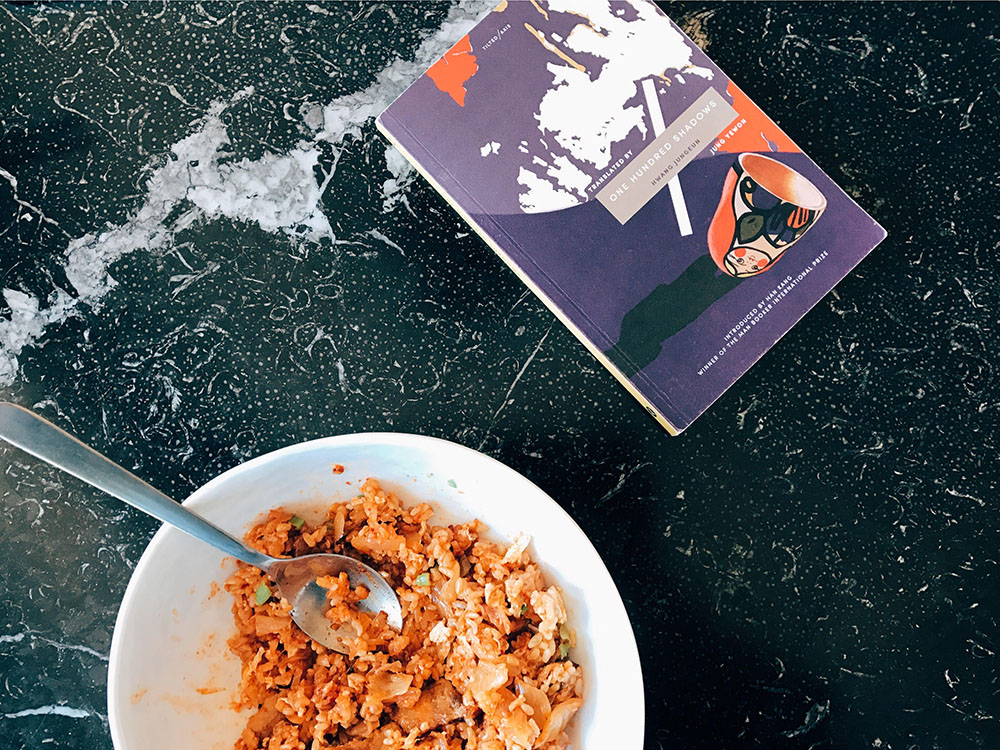

hwang jungeun, one hundred shadows (tilted axis, 2016)

one of the things that i love about korean literature is that it often seems to exist in a korea different from the glittery, technologically-advanced, prosperous, high-achieving state that korea seems to present itself as. hallyu shows off a romantic view of korea, with its cutesy, perky pop stars and shiny dramas, a lot of which has been the product of the government pouring resources into hallyu and generating an idol-making machine within its entertainment industry, while literature has gotten considerably less attention until recently.

i don’t want to go so far as to claim that, as a result of that, korean literature took on different tones (though i have heard that theory before), especially as there is also the question of what and how literature is translated. is it that the gatekeepers to translation just have a love for korean literature that tells narratives of those who exist on the fringes of society? who bear witness to the startling wealth gaps that exist in sometimes jarring juxtaposition in korea?

regardless of whether it’s a translation thing or a trend in korean literature, i’m glad that this literature exists. i’m glad that there are writers out there who aren’t enthralled with this one depiction of korea, who write novels that go beneath the glossy veneer and explore the effects of prosperity, who write about people who exist outside the aspirational “norm.”

hwang jungeun’s one hundred shadows is one such novel.

the novel is set primarily in an electronics market in korea, and it’s a rundown market, one that developers want to tear down and build into something new. unsurprisingly, they use all kinds of means to try to bully the storeowners to leave, whether by convincing them to take a sum of money and relocate their shop in some unclear new location or by blocking off the main entrance of the market so customers believe they’re closed. it’s not that hwang focuses on this aspect of the story; one hundred shadows is largely a story about two characters who work at different shops in the market; and it’s a story, also, about the people in this market, these people who don’t have much, who exist on the outside edges of an upward society, who are trying to resist the shadows that rise and threaten to consume them.

i think that’s the strength of the novel, though, that hwang tells the story of these economic differences in korea without directly telling them. she doesn’t get into social issues or into the nitty-gritty of the conflicts that might exist between these shop owners and the developers — the details are there if you read for them in the way that these stresses and worries are present in and shape people’s lives without necessarily taking center stage.

… for me this whole area is inextricably tangled up with those memories and the way they make me feel, and when i hear people call this place a slum, well, it just doesn’t seem right to me. calling a person poor is one thing, that’s an objective fact in a way, but ‘slum’ … mujae trailed off.

i wonder if they call this kind of place a slum because if you called it someone’s home or their livelihood that would make things awkward when it comes to tearing it down. (hwang, 102)

sometimes, i read sentences and laugh a little to myself because i wonder how they must read in korean, how much of a tangle they must have been to translate. other times, i read sentences that make me wonder what the original korean is, what kinds of decisions the translator must have made and why, what kinds of liberties the translator may have taken. other times, i read sentences that make me sad because i’m sure a lot was lost in translation, that the korean must be achingly beautiful in the ways that korean can be, in the ways that english cannot.

i love the korean language. it’s lyrical and poetic, and you can run the language around in these exquisite loops that seem like they can go on forever without losing themselves. i love the lack of clear third-person pronouns, and i love the ambiguity you can create because pronouns aren’t necessary — in korean, the subject pronoun is often implied, a quirk about the language that is used to create ambiguity in quiet, powerful ways.

i love the words themselves, too, and, sometimes, when i think of korean and i think of english, i find myself thinking how limited a language english is. there are words in korean that cannot be found in english, that require a paragraph just to try to define; there are ways to feel in korean that do not exist in english; and there are ways of encompassing a national identity that cannot be so clearly distilled to be consumed and understood.

in general, i love how much language can reflect culture, and i’m fascinated by and interested in the act of translating, how it’s an act of loss, not simply of words but of culture and history and societal context. this is one of the reasons i love reading korean literature-in-translation, too, because the very fact of it being translation — crucially, of it being translation from korean, a language and culture i know to a certain degree of intimacy — alters the reading experience. in many ways, i feel like i am a much more active reader when it comes to translated korean literature, and that is something i appreciate.

i don’t really like people who go around saying they don’t have any debt. this might sound a little harsh, but i think people who claim to be in no debt of any kind are shameless, unless they sprang up naked in the woods one day without having borrowed anyone’s belly, and live without a single thread on their back, and without using any industrial products. (hwang, 18-9)

han yujoo, the impossible fairy tale (graywolf press, 2017)

choi mia had two fathers. she received twice as many presents as the other children received on birthdays and christmas. she had no siblings. the other children were jealous of her face, clothes, and school supplies. she has never been jealous of other children. choi mia was not given enough time to learn about jealousy. (han, 92)

there is a beauty to the way han yujoo writes violence in the impossible fairy tale — or maybe “beauty” is the wrong word because it’s not that she makes it beautiful or tries to render it so. she’s brutal about it, writes about it in ways that make you flinch, but she does it indirectly without giving way to sensationalism or even without putting it into clearly defined words.

i can’t even figure out a way to summarize this book, maybe that it’s a story about two children, one who has everything and one who does not. it’s a story about violence against children, about the violence children are capable of, about the way violence begets violence in the way that violence is trauma that is felt on every level. it’s a story about how we all must find outlets for our fear, our anger, our desperation — or that, even if we don’t, if we try to suppress everything, things will somehow escape, sometimes to catastrophic results.

somehow, that’s not even the most interesting part of the book, though, because han does a pretty damn stellar pivot with part two, bringing us into an i-narrative voice. it’s unclear who this “i” is, though; is she one of the students in part one? is she one of the two children? what are these dreams she keeps writing about? who is she? why are we suddenly looking at things from her perspective? why am i automatically assigning the female gender to her?

at first, i thought the dream sequences in part two were going on for too long, wondered if han weren’t falling prey to art for art’s sake, ambiguity for ambiguity’s sake, which is a particular peeve of mine. i don’t want to discuss any details because i don’t want to give any of it away, but part two unfolds in surprising, thoughtful ways that make the meandering worthwhile.

reading, after all, is an act of trust; to a certain degree, we need to be able to trust the author. we need to be able to trust that she’s taking us on a worthwhile journey (“worthwhile” being entirely subjective), that she is thoughtfully using language, that she knows what she is doing, the story she is telling. we need to be able to trust that she purposefully created this experience for us, that none of these choices is casual or lacking in deliberation. we need to be able to trust that she will raise questions that she will answer satisfactorily, that she isn’t abusing her position as author and creator to send us in circles without reason.

han asks us for this trust, and she asks a lot of questions about what it means to create. she asks what these lives are that we, as writers, as artists, create and give body to, these characters we build and into whom we infuse life and personality quirks and histories. she asks about the limitations of creating, of fiction, of story; she asks about the responsibility of these acts of creating.

she doesn’t necessarily give us any hard answers to any of these questions, though, but that doesn’t mean she leaves us dissatisfied. the questions she’s asking aren’t meant to have hard answers, anyway. they’re meant to get us questioning, to make us active readers, cognizant of the ways in which we might be complicit in the actions of these characters, because the point, as always, is to consider.

in this way, the sole objective of the stories i want to tell is to throw you into an unclear state, to make you believe while you’re not able to believe. (han, 150)

i feel like noting that han does some really interesting things with language in the impossible fairy tale, and i’m so curious (01) to read this in korean and (02) how the translator, janet hong, made some of the decisions she did. i don’t mean the latter in an accusatory way or to imply that she did a bad job; i’m genuinely curious because i love language and have dabbled in translation and regard it with a fair amount of wonderment.

bandi, the accusation (grove press, 2017)

i confess that i have yet to finish reading the accusation. that is not going to stop me from writing about it now, especially as it is a book i am certain to revisit in the future.

bandi is the pseudonym for a north korean writer currently still living in north korea, and the accusation is a collection culled from a manuscript that he has been writing for years. the manuscript was smuggled out of north korea, an action that put not only bandi’s life but also the lives of everyone involved in danger. it was bandi’s hope that his stories be published in south korea, but he never dreamed that they’d be translated and be read outside of korea.

the accusation was published in south korea in 2014. it is published by grove press in the US and serpent’s tail in the UK on tuesday, 2017 march 7. bandi, in korean, means firefly.

as may be inevitable, we give certain books more weight than others, and the accusation certainly is one of such book. as crucial as journalistic and investigative stories about north korea are, as important as memoirs by refugees are, there is a void when it comes to fiction, and i am glad to have this collection.

because here is where i get down to story: i often get annoyed by people who constantly try to downplay the humanities, sneering at books and literature and fiction like they’re mere child’s play. part of this is that i grew up in an environment that considers fiction useless; the korean phrase used to dismiss fiction is “쓸떼 없다,” which translates literally to “there is no use for that.” even now, i continue to be told that the books i read are pointless, that they’re making me see the world in negative ways, that i need to read more essays, more philosophy, more non-fiction, less stories.

and yet.

stories are the means through which we see the world. they are how we see ourselves in the world, and, similarly, they are how we see others in the world. stories are how essays, philosophy, and non-fiction are structured; stories lie beneath food, art, music. stories are part of our everyday lives as well — when we go home and talk to our family, our friends, we tell them stories from our days at work, at school, at wherever. when we meet new people, we tell them stories about ourselves — where we’re from, what we do, who we are. when we give a presentation, make an argument, think about our futures, we are telling stories, and, when we write, when we create, we are doing just that — we are telling stories, stories about ourselves, our obsessions, the circumstances of our lives.

you might ask, “if stories are in every part of life, then why do we need fiction?” the thing is that, sometimes, fiction allows us to go places that non-fiction doesn’t. sometimes, fiction opens up barriers that might exist in non-fiction that make some stories impossible to tell. sometimes, fiction makes it easier for us to explore darknesses and fears and truths that we might not otherwise confront.

similarly, sometimes, fiction opens up windows to communicate with others, to provide people opportunities to open their hearts in ways that non-fiction cannot. sometimes, fiction makes it easier to consider a new way of seeing people, to empathize in deeper, more personal ways, to realize that we are all people — we are all human, and we all exist on this planet, and we can work to make things better for each other.

by tapping into our empathetic selves, fiction challenges us to feel and, in doing so, hopefully challenges us to be better people and to do good. it hopefully challenges us to see the people hidden behind an oppressive regime and see them as people.

in the afterword to the accusation, kim seong-dong, a writer for the monthly chosun, tells us this: that bandi started by joining the chosun literature and art general league in north korea, that he was published in various periodicals but came to a realization that led to the stories in this book.

and yet, something began to weigh on him: the great famine of the early to mid-1990s, exacerbated by floods but stemming from the disastrous economic policies of previous decades, which the government insisted on referring to by the officially mandated code words “the arduous march.” witnessing scenes of misery and deprivation, in which many of his friends and colleagues perished, provoked him to reflect deeply on the society in which he lived, and his role there as a writer. a writer’s strength, he found, is best deployed within writing. and so he began to record the lives of those whom hunger and social contradictions had brought to an untimely death, or who had been forced to leave their homes and roam the countryside in search of food. now, when bandi picked up his pencil, he did so in order to denounce the system. (232-3)

&

rather than himself trying to escape from north korea, the writer bandi has sent his work out as an envoy, risking his life in the process. surely this is because he believes that external efforts can transform the slave society he lives in more quickly than internal ones. on handing his manuscript over, bandi said that even if his work was published only in south korea, that would be enough for him. this work should be heard as an earnest entreaty to shine a spotlight on north korea’s oppressive regime. (241)

i sincerely hope that the accusation is received accordingly. i will definitely be revisiting it in the future.

whether something is harmful or not is a matter of personal standards. (hwang, 57)

to be honest, while one of the reasons i started this weekly post series was very much to fight back against a toxic administration, another reason was purely selfish: to give myself a sense of purpose and something to fight for outside the brokenness in my brain and my body.

i live with what is called major depressive disorder, recurrent episode, and panic disorder, and i also struggle with suicidal thinking and hopelessness and general despair. i go to sleep at night hoping i won’t wake up in the morning, and i wake up in the morning disappointed to find myself still here. add onto that that i was also recently diagnosed with type 2 diabetes*, so there’s that extra dose of self-loathing added onto everything else, especially when food was that one last comfort i had, that one last lifeline i was holding onto to get me through the days, to get me out of bed and try to care for myself. all of that, with one blood test, is gone — or, at least, altered beyond what i am currently able to handle.

most days, i find myself helpless, unable even to make that effort to care. when i check my blood sugar and my meter gives me back that triple-digit reading despite it only being a week of monitoring and trying to bring my glucose down, i don’t know what to do, so i shut down, stop eating, hope this kills me. maybe it goes without saying that i’m still processing the anger and resentment that comes with this diagnosis, letting the mental temper tantrums run loose when the numbness wears off, and trying to tell myself that it’s not that big a deal, it’s manageable, it’s not life or death — but, truth be told, i hate that, i always have — it’s just another way for people to enforce shame via diminishing, blaming, belittling.

because here’s the truth: something doesn’t have to endanger your life to threaten it, and just because something is manageable doesn’t mean that it isn’t devastating. context matters. the whole of a person matters. and had this happened at some other point, when i wasn’t already so broken, so empty-handed, so hopeless, i might have reacted differently. i might have squared my shoulders and said, okay, and simply dealt with it. but it didn’t — it happened now, and, when all the pieces of my life are lying in shambles at my feet, it’s impossible to take this in stride and get on with it, even as i know that, given time, i will learn to live with it.

so that’s a long-winded way of saying that i won't be continuing these thursday posts. i won’t stop blogging and will continue posting regularly, but, as of this moment, i am not able to continue this once a week schedule. for one, i barely have the ability to focus these days, much less finish books at the pace i did before and write posts with such tight turnaround time, and, for another, even as i know that this is disappointment in myself speaking, a huge part of me, frankly, doesn’t really see the point. thank you for following along thus far; it means more to me than i can express.

* for anyone concerned, i made my kimchi fried rice with brown rice. also, i am new to this and still figuring out what works and what doesn’t.