wick tells me we live in an alternate reality, but i tell him the company is the alternate reality, was always the alternate reality. the real reality is something we create every moment of every day, that realities spin off from our decisions in every second we’re alive. i tell him the company is the past preying on the future — that we are the future. (318)

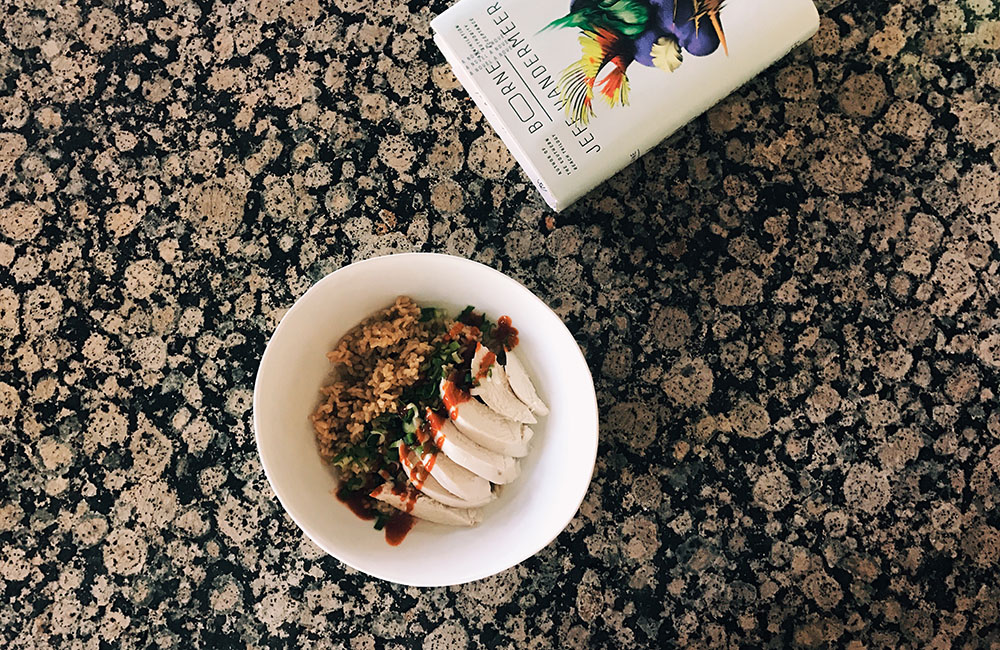

a spot of comfort, a spot of familiarity: this is my bastardization of hainanese chicken rice.

i love hainanese chicken rice; i’d go eat it every 2-3 weeks back home in nyc; and, one day, i looked it up on a whim to see if i could make it at home. i eat mine like soup because i love the broth — it’s gingery, garlic-y, scallion-y — and, though my version isn’t quite like the delicious hainanese chicken rice from nyonya, it’s the dish i crave when i’m feeling under the weather or in need of comfort.

it was the perfect thing to cook last week in an attempt to perk up my appetite.

that’s the problem with people who are not human. you can’t tell how badly they’re hurt, or how much they need your help, and until you ask, they don’t always know how to tell you. (148)

i feel like i’ve spent a fair amount of time in recent months talking about books that are relevant to our times, so it might sound like that’s all i’ve been reading. part of that has been deliberate, given the times we live in, but a good part of that has been unintentional — i’m not necessarily the most intentional of readers. i don’t plan out what i’m going to read when; i don’t make or follow a schedule or reading plan; and, sometimes, most times, this happens — i get super excited for a book, run out and buy it immediately, and don’t actually get to it for months.

(i think publishers might find that annoying, especially when they’ve been generous enough to send me books, especially when i’ve requested them. sometimes, i will just sit on books, though, not because i don’t like them but because i’m not quite in that particular mood or place.)

this was not the case with borne (FSG, 2017), though. i pretty much devoured it once i had it in my hands. (note that i did purchase my own copy.)

what jeff vandermeer does particularly well is build very smart, complex, vivid worlds. reading vandermeer is often like getting drunk on language, the ways he conveys the physicality of his worlds, the strangenesses, the colors, the smells, and, as i was reading borne, i’d get wrapped up in his visuals, these rich, evocative passages, feeling like the words themselves were undulating beneath my fingertips, beneath my eyes.

he’s such a visceral writer, and this is something i loved so much about his southern reach trilogy as well — how vibrant and alive everything is, how much tension seems to throb on the page. his writing fairly breathes, though i do wish that, pace-wise, borne had moved a little faster, had been a little more tightly wound. i did feel that the novel had a slight lag at parts, felt a little too heavy in moments and weighted down for it, but these are small criticisms, i want to say, because vandermeer has created a novel of wonder.

and god damn, that closing passage is so good.

whenever i make this dish, i keep saying i’m poaching a chicken, but that’s a lie. i boil it, but it sounds so much better to say “poached chicken” than “boiled chicken.” i mean, “boiled chicken” just does not sound as appetizing.

there isn’t much to this at all. you buy a chicken, not a giant one, 3-4 pounds is good (it’s terrifying, the gargantuan chickens you find these days). i rub the skin over with coarse sea salt to give it a scrub and buff it out, though i don’t know if i’d say that’s a strictly necessary step, so you could just give your chicken a good pat-down with a paper towel or two, and peel some garlic, chop up some scallions (in thirds), and cut off a knob of ginger. stuff all that into the chicken’s cavity (that you have washed), and put the whole thing into a pot and drown it with water.

and then, boil.

one of the things i love about vandermeer’s novels is that he raises a fair number of questions about what it is to be a human existing in the world-at-large — in the case of borne and the southern reach trilogy (which i loved and wrote about here), the world gone wrong. he asks about the effects of greed and experimentation on the world, about technology, about corporate power and control, and he asks who we are, who we’ve become within everything gone awry.

one key question raised in borne is: what does it mean to be a person? the follow-up to which is, and does it matter?

it sounds like a question with an obvious answer — a person is a human, homo sapien, upright, four-limbed creature with opposable thumbs, individual will, cognitive capabilities, and the ability to feel — and, maybe, by all rights, it should be a question with an obvious answer.

however, as it goes, personhood in itself is complicated. the human race is one that has, since its inception i dare say, sought power and dominion, whether over the earth itself or over each other, which assumes that one group is superior to others. we create Others of people who don’t look like us, want like us, think like us, and we seek out the familiar and create cliques and cause division. to some degree, you might argue that this is natural; it’s an instinctive impulse for survival and for comfort and strength. you might also argue that we are all guilty of snap, surface judgments, of comparing ourselves to each other and creating contrasts in those ways. to some degree, you would be right.

the extreme end of that, though, is that we dehumanize the Other because, by putting ourselves above them, by elevating ourselves and exploiting our positions of privilege and power, we make ourselves superior, and we make them less than human.

we make them not a person.

in vandermeer’s novel, borne is clearly not a person, not physically. he is a creature that the narrator, rachel, finds when she is out scavenging in the post-apocalyptic world (i’d argue it’s fair to describe it as such) in which borne is set. she’s stalking mord, the giant bear monster/creature that has wreaked havoc upon the city, after having been created himself by the company that was the catalyst for all this destruction, and she finds borne in mord’s fur. intrigued, she names the creature borne and takes him home to the balcony cliffs, a former apartment complex, where she lives with wick, a former employee of the company.

borne is not human; he is an entity, a living, cognitive being that can change at will, assume other forms, and mimic via consumption. he can shape shift and cast light and grow, and he can read and feel and be sarcastic and want to be part of a family. his physical form makes it clear that he isn’t human, though, that he is, rather, something that was clearly created, something that came from the company, something that wick wants to take apart and break down into parts because borne is suspect — he could be a weapon; he could be a spy; his physicality automatically renders him a threat, something not to be trusted.

to rachel, though, borne is a person. he thinks. he feels. he wants. she considers him her child, having taken care of him since he was a wee creature and watched him grow, witnessed him experiencing the world, being wounded, learning deception. vandermeer, too, doesn’t challenge borne’s personhood; whether borne, specifically, can or cannot be a person isn’t really the central question of the novel.

rather, it’s the question of what constitutes a person in general. does personhood demand physical familiarity? and, if we were to argue that it’s physical familiarity, what, then, of the people who don’t look like us, who have different skin colors, hair textures, physiques? is it, then, an internal commonality? but what about those of us who don’t share the same worldview, worship the same god (or any god at all), want people of the same gender? is it about sharing the places we’re from, the things we want, the morals we embody?

where does familiarity begin, and where does it end?

with your chicken in the pot, bring the water to a low boil, then turn the heat down to medium-low. you want your soup to simmer for 30 minutes, during which you want to skim, skim, skim. get off the scum that rises to the surface, the fat, the oil.

to be honest, i don’t know why i cook a chicken with the skin on; i throw the skin away, anyway.

season with salt. taste, skim, simmer.

i’d been teaching him the whole time, with every last little thing i did, even when i didn’t realize i was teaching him. with every last little thing i did, not just those things i tried to teach him. every moment i had been teaching him, and how i wanted now to take back some of those moments. how i wanted now not to have snuck into wick’s apartment. how i wished i had been a better person. (191)

sometimes, i think that it’s easy to look at dystopian fiction (or sci-fi or war stories) and think, “oh, i would never.” i would never kill someone to save my own life. i would never leave someone outside to die. i would never do just about anything to survive; i would have limits; i would never cross the boundaries of decent humanity.

and that’s not restricted to attitudes toward fictional characters or war stories or whatever because it’s easy to look at anything, any situation, and think that — oh, i would never get an abortion. i would never physically assault someone. i would never exploit a vulnerable person. i would never be so cruel. i would never do this, i would never do that, i would never.

it’s easy to self-elevate ourselves onto some moral high-ground, when, yet, the truth is that we are all capable of great violence, and we are all capable of committing horrendous acts of harm and damage. we are all capable of giving in to our worst selves and doing all kinds of fucked up shit if it means self-preservation, if it means survival.

and this, too, is a way that we deny people personhood — by saying, “oh, i would never” and constructing false boundaries that create Others and keep them out. it’s a mentality that hurts us, though, because, when we try to block off the uglinesses that inform our own personhood, we will never be better — we will never exist together.

and, yet, it is easier to hide in that i would never. i would never resort to that. i would never act like that. i would never have done this that time if it hadn’t been for this.

i would never.

instead, i lay in my bed in my apartment, doubled over and sobbing until i hurt from it, wanted to hurt from it. i didn’t care what happened to me. mord could have dug me up and swallowed me whole as a morsel and some part of me would have been grateful. and yet there was another part of rachel, the part that had lasted six years in the city, who waited patiently behind the scenes, saying, get it out, get it all out now so it doesn’t kill you later. (187)

the thing about hainanese chicken rice is that you cook your rice in the broth, not in water, which means that you cook your chicken before you start your rice. which is fine because hainanese chicken rice is eaten at room temperature.

roughly 30-45 minutes in, poke your chicken in the thigh. if the juices run clear, it is done. remove the chicken very, very carefully from the broth; i usually do this with tongs and a giant spoon, trying to drain as much broth from the chicken as i can before moving it quickly to the cutting board i’ve placed as close to my pot as possible. rub some sesame oil onto the skin of the chicken, not a whole lot because sesame oil is not a subtle flavor and a little goes a long way. let the chicken rest and cool.

ladle broth into your rice (which you should have washed) (jasmine rice is my favorite for this dish), and cook. chop some scallions while you wait. also watch for for broth puddles emitted by your chicken.

my main takeaway from borne, though, is this — it is important for us to retain a sense of wonder.

no matter how shitty the world gets, no matter how much it falls apart, and no matter how fucked up our lives become, there is always something in the world to maintain wonder, and it is important for us to hold onto that.

when borne is still a child, rachel is taken away by how he finds the world beautiful. the world in the novel is a toxic one, the river poisonous sludge, the city laid waste by mord and riddled with traps. it’s a world of dangers and hazards, where rachel has no idea how long she and wick will be able to continue defending and surviving in the balcony cliffs, where animals and humans are both engineered to be vicious, killing monsters.

it is a world you might look at and see nothing but horror and destruction.

and, yet, borne looks out at that world and sees beauty.

we went out on the balcony. borne pretended he couldn’t see through his sunglasses and took them off. his new mouth formed a genuinely surprised “o.”

“it’s beautiful,” he exclaimed. “its beautiful beautiful beautiful …” another new word.

the killing thing, the thing i couldn’t ever get over, is that it was beautiful. it was so incredibly beautiful, and i’d never seen that before. in the strange dark sea-blue of late afternoon, the river below splashing in lavender, gold, and orange up against the numerous rock islands and their outcroppings of trees … the river looked amazing. the balcony cliffs in that light took on a luminous deep color that was almost black but not, almost blue but not, the jutting shadows solid and cool. (56)

sometimes, i go on twitter and wonder why the fuck i went on twitter in the first place. everything’s a total shitshow, whether it’s whatever’s going on in DC, in korea, in local governments here, and i’m constantly asking myself what the fuck is happening, if this is really the world we’re living in.

similarly, sometimes, given all the crap going haywire in my brain and my body, i get lost in despair, in the swallowing hopelessness that this is forever — my depression, my anxiety, my ADHD, my diabetes — these are disorders and limitations i am going to have to live with forever, and, sometimes, on my bad days, it all becomes too much to handle.

it’s easy to get tired, to want to give up and give in, but, then, i look up at the sky, and it’s streaked in the most marvelous, dramatic colors. i go to the ocean and watch the waves crashing into the shore, look out at that horizon and think, awed, at how magical that line is where the sky meets the sea and the possibilities seem endless. i walk down the street and see spring all around me, the flowers bursting in colors, the sun making shadows dance beneath my feet, the way life comes around full-circle.

and that, i think, is wonderment, not an overblown, grandiose attempt to cast the world in a veneer of false gold or to see silver linings everywhere — i fucking hate silver linings. i don’t mean wonderment in the sense of forcing yourself to look for it, to see it everywhere, to maintain a sunny, delusional attitude that there is always something good to be found in the shit. sometimes, shit is just shit.

however, it is another thing to remain open to the possibility of wonder, and i think that is crucial because wonderment is linked with the ability to hope. we cannot hope if we do not believe that there is something worth hoping for, and keeping ourselves open to wonder is one way of keeping that hope alive.

a few weeks ago, i shared a post on instagram with the caption:

one of the things i will always find hopeful is my ability to recognize and appreciate beauty because that's something depression takes away. and, as much as i love the beauty of mountains, my heart is most at ease by water.

i fully believe this, and i oftentimes believe that the only reason i am still here today is that wonder. it is my ability to look at the world around me and still see it to be a beautiful place, to find that somewhere in me lies a heart that is still beating.

because, even in the worst of my depression last year, when i was suicidal and so close to taking my own life, i would go on these long walks around brooklyn. i’d walk over to brooklyn bridge park, to prospect park, all over park slope and cobble hill, and, as i would walk and walk and walk, sometimes, i would ache so badly inside because it hurt how beautiful i still found the world. at that time, in those moments, i wanted so badly for all this pain to be over, for my life to be over, and i’d sit on a bench somewhere and look at the world around me and breathe in the air and think that, god damn, i was hurting so badly inside, and my world felt so small and so dark and so impossible, but there was this world, this city, outside me, outside my pain and hurt and despair, and it was beautiful and good, and my ability to recognize that and respond to it must mean that there was still a part of me that wasn’t willing to die.*

* by no means am i trying to imply that going on long walks and appreciating the world around you are enough to get over suicidal depression. that couldn not be farther from the truth. it’s taking me weekly therapy appointments, monthly meetings with my psychiatrist, medication, meals with people i love, a lot of generosity and kindness for myself. it’s taking me books and food and cooking, routine, instagram, events, family. it’s taking everything just to stay alive.

when your chicken is cool, carve it or shred it with your fingers or dissemble it how ever you prefer. spoon some rice into your dish, top with chicken, ladle some broth over it, top with minced scallions, and eat with sri racha. there’s a sauce you could make instead of just resorting to plain sri racha, but i’m too lazy for that. oops.