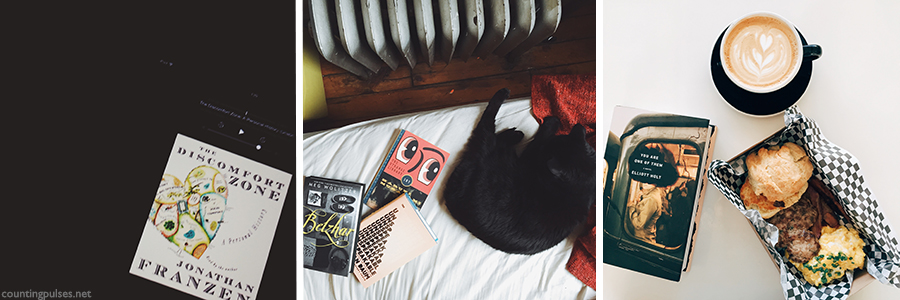

december reads! end of 2014! this year went by so fast …

fifty-four. the strange library, haruki murakami.

at the same time, my anxiety had turned into an anxiety quite lacking in anxiousness. and any anxiety that is not especially anxious is, in the end, an anxiety hardly worth mentioning. (19) (no page numbers so section number)

this was … weird. (which i guess kind of goes without saying.) to be honest, i’m not sure if i liked it or not. and, to be even more honest, i’m not sure if there’s anything that much deeper to it — it’s a strange little book, and that’s what it was meant to be.

… apparently, that’s all i have to say about it. the strange library was interesting to pick up as a visual reading experience because of the way it was designed, and i’d recommend it as such — an interesting visual reading experience.

fifty-five. belzhar, meg wolitzer.

“everyone,” she [mrs. quenell] continues, looking around at all of us, “has something to say. but not everyone can bear to say it. your job is to find a way.” (34)

belzhar was an easy, quick read, and i liked a lot of the ideas in it — the boarding school for kids recovering from trauma or working through struggles/disorders, a world within journals where the characters can return to the days before their lives were flipped upside down, the juxtaposition of this static but desirable world of the past and the vibrant but unbearable, changed world of the present. i liked the struggle that came with that, the inevitable point of having to learn to let go and return to the present.

i have mixed feelings about the book, though. i wished wolitzer would dig deeper; everything felt like it was held on the surface of things; and the stakes honestly didn’t seem high enough, particularly for the narrator. and i’m mixed about the twist at the end because i’m not that convinced of it? and the ending was too hopeful, too neat and clean; i honestly kind of just shrugged it off.

all in all, though, it was an easy, quick read, and i enjoyed it enough.

fifty-six. the unspeakable, meghan daum.

after more than a decade of being told that i’d wake up one morning at age thirty or thirty-three or, God forbid, forty, to the ear-splitting peals of my biological clock, i’d failed to capitulate in any significant way. i would still look at a woman pushing a baby stroller and feel more pity than envy. in fact, i felt no envy at all, only relief that i wasn’t her. (“difference maker,” 116)

i liked how the “unspeakable” things in this collection weren’t big, dark, giant secrets — daum isn’t tackling hugely controversial or necessarily new topics; she’s talking about them with more honesty and candor than might be expected. like, she doesn’t try to “make excuses” for choosing childlessness or gloss over the intensity of the dog owner-dog relationship or tell some grand tales laden with epiphany or emotion from the mysterious illness that put her in a coma and close to death a few years ago — and, in such ways, i feel she tackles the unspeakable. she does it in very engaging, frank, and funny writing, too, without going on the defensive (or even feeling like she should be defensive), and i appreciated this collection and daum’s for their openness.

it’s interesting to think about how things become “unspeakable” — or, more specifically, in what ways things become “unspeakable.” we can talk about things all we want, but when there’s a barrier of emotional expectation or societal niceties, then how much are we really talking?

fifty-seven. station eleven, emily st. john mandel.

hell is the absence of the people you long for. (144)

if i had to describe station eleven in three words, i’d call it beautiful, haunting, and hopeful. it’s a world that’s essentially been “reboot” by a virus that killed off millions (i’m assuming) more or less overnight and thus saw the end of technology and electricity and other such “basic” things we’re accustomed to. even so, it’s not a book of despair, and it’s not a story of mere survival either but of people who are making their lives in a changed world and finding hope and togetherness and purpose — and i loved how mandel tied together all the different characters and mapped out how they were connected in the “previous” world.

i loved the days i spent immersed in this world.

fifty-eight. the twenty-seventh city, jonathan franzen.

poverty, poor education, discrimination and institutionalized criminality were not modern. they were indian problems, sustaining an ideology of separateness, of meaningful suffering, of despairing pride. in the ghetto, just as in the indian ghettos of caste, consciousness would come slowly and painfully. jammu had no patience. she’d hauled the big industrial guns into the inner city and called it a solution, because ultimately it was far easier to change the thinking of a rich white fifty-year-old or to deflect the course of his eighteen-year-old daughter than it was to give a black child fifteen years of decent education. (399)

when i first read the twenty-seventh city a few years ago, for some reason, i went into it thinking it was sci-fi. i’m not sure why i thought that — i actually kind of blame it on the picador cover — but i did, so i was so fucking confused for the first hundred pages, wondering where the sci part of it was, which meant that the whole novel was kind of lost to me. i’ve read (or reread) franzen’s othernovels this year, so i figured i might as well round it out with the twenty-seventh city, which is his first.

to be quite honest, i couldn’t quite get into it this second time around, though i also can’t fully remember what i thought of it the first time around because i was so confused. the short, clipped sentences drove me kind of batty, and i didn’t like all the conspiratorial stuff of the new police chief coming into st. louis and trying to amass power, and i hated singh for being so dastardly and casual with violence to achieve these conspiratorial ends and i also hated jammu for pretending to be above the dirty, sneaky crap singh would do, like she could keep her hands clean.

i also hated the ending. i almost stopped reading because i hated it — it was unnecessarily violent and jarring in the narrative, too, and i just did not like it.

fifty-nine. the discomfort zone, jonathan franzen. (audiobook)

adolescence is best enjoyed without self-consciousness, but self-consciousness, unfortunately, is its leading symptom. even when something important happens to you, even when your heart’s getting crushed or exalted, even when you’re absorbed in building foundations of a personality, there come these moments when you’re aware that what’s happening is not the real story. unless you actually die, the real story is still ahead of you. this alone, this cruel mixture of consciousness and irrelevance, this built-in hollowness, is enough to account for how pissed off you are. you’re miserable and ashamed if you don’t believe your adolescent troubles matter, but you’re stupid if you do. (“centrally located,” 113)

my first audiobook! i’ve discovered that audiobooks are awesome for plane rides! though maybe i specifically mean audiobooks recorded by franzen himself because i love his voice (it’s so throaty and deep and hoarse), and i’m sad that he hasn’t recorded more …

listening to an audiobook is [obviously] a different experience. i’d already readthe discomfort zone twice before, so i wasn’t listening to it for the first time, so it was interesting to experience the book in a different way, especially because franzen adds his own tone and [physical] voice to it. it’s also different listening to him read on audiobook because i feel like he’s more intense “in real life,” reading faster and more fluidly whereas, on audiobook, he had to slow down and be more rigid in pace.

sixty. slouching towards bethlehem, joan didion.

that is a story my generation knows; i doubt that the next will know it, the children of the aerospace engineers. who would tell it to them? […] “old” sacramento to them will be something colorful, something they read about in sunset. […] they will have lost the real past and gained a manufactured one […].

but perhaps it is presumptuous of me to assume that they will be missing something. perhaps in retrospect this has been a story not about sacramento at all, but about the things we lose and the promises we break as we grow older […]. (“notes from a native daughter,” 185-6)

my first didion! didion’s writing has an ethereal, dreamy quality to it, even when she’s covering trials or immersing herself in san francisco’s haight-ashbury or writing about sacramento. i like the way she writes about california — there’s a tenderness and affection to it — and it makes me think of california in different hues, too.

sixty-one. you are one of them, elliott holt.

there is something painfully honest about winter: the skeletal trees, the brutal repetition of the cold. there are no empty promises, no hazy, humid hopes. it’s reality, lonely and stark. (198)

last book of the year! i loved holt’s depiction of childhood friendship and the tangles of it and how the spectre of it can loom over you, and the russian and descriptions of russia poked at my yen to travel. it felt a little anticlimactic, though, and i wanted more conflict, more tension, more emotion, actually, on the narrator’s end. i loved the ending, though, especially because i was all set to be disappointed in the narrator, so i was proud of her for actively pursuing a decision and effectively shedding her past.

this was a good book to end the year on, and i’m pleased to say that it’s been an awesome reading year, and it’s been such a pleasure to be able to read more and to practice reading more thoughtfully. i know i’m still not that great at writing about books, but i’m glad to be challenging myself to try to get better at it!

thanks for being with me through the year! and now i go off to write my year-end recap …!