this is why i like the end of the year. >:3

in 2015, i read 68 books*, and here are my top 7 from those 68 (in no particular order) (or, rather, in the order i posted them on instagram, which was in no particular order).

- helen macdonald, h is for hawk (jonathan cape, 2014)

- alex mar, witches of america (FSG, 2015)

- patricia park, re jane (viking, 2015)

- rebecca solnit, the faraway nearby (penguin, 2014, paperback)

- jonathan franzen, purity (FSG, 2015)

- han kang, human acts (portobello, 2016)

- robert s. boynton, the invitation-only zone (FSG, forthcoming 2016)

(you can find quotes and reasons why i chose these 7 on my instagram.)

* as of this posting time. i still have two days to read more!

in 2015, i went to 38 book events and readings, and here are 10 i particularly enjoyed.

- marie mutsuki mockett and emily st. john mandel with ken chen at AAWW

- michael cunningham at columbia

- meghan daum with glenn kurtz at mcnally jackson

- kazuo ishiguro and caryl phillips at the 92Y

- aleksandar hemon with sean macdonald at mcnally jackson

- alexandra kleeman and patricia park with anelise chen at AAWW

- lauren groff at bookcourt

- jonathan franzen with wyatt mason at st. joseph's college

- patti smith with david remnick at the new yorker festival

- alex mar with leslie jamison at housingworks bookstore

(both franzen events had no-photo policies.)

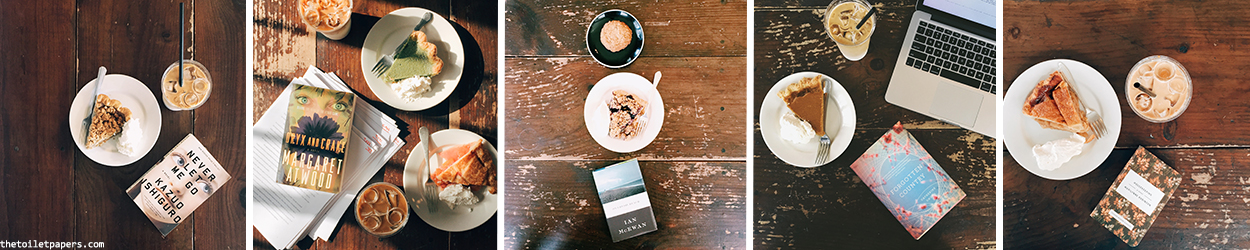

in 2015, i took 34 photos of books with pie. mind you, this is not the number of times i ate pie. this is simply the number of times i went to eat pie and decided to photograph it with the book i was reading at the time. and by pie, i mean pie from four and twenty blackbirds because their pie is delicious and not too sweet and totally worth going to gowanus for (so, if you're in nyc, go get some!).

here are 5 photos of books with pie because it would be unnecessarily mean of me to torture you with all 34 slices of amazing pie, wouldn't it?

in 2015, i took 38 photos of books with stitch.

i suppose, to provide some context: i love stitch. lilo and stitch is one of my favorite movies (we're talking top 3 here). i've had this stitch for 13 years. i still shamelessly take him with me everywhere (he's in california with me right now). obviously, he popped up every now and then with a book.

here are 5 photos of books with stitch. i'm totally choosing how many photos to post arbitrarily (in multiples of 5, though, so maybe not so arbitrarily?).

in 2015, my book club started, and we read 10 books. we've now eased into a routine of meeting at my friend's apartment and having a potluck, but we were absent this routine the first two times we met, hence the three out-of-place photos. i know; it's making me a little twitchy, too; but we'll have 12 consistent flat-lays from 2016!

- marilynne robinson, lila (FSG, 2014)

- alice munro, the beggar maid (vintage, 1991) (first published 1977)

- kazuo ishiguro, an artist of the floating world (vintage,1989) (first published 1986)

- margaret atwood, the stone mattress (nan a. talese, 2014)

- jeffrey eugenides, the virgin suicides (picador, 2009) (first published 1993)

- ta-nehisi coates, between the world and me (random house, 2015)

- virginia woolf, mrs. dalloway (vintage, 1992) (first published 1925)

- michael cunningham, the hours (FSG, 1998)

- nikolai gogol, the complete tales (vintage, 1999)

- nathaniel hawthorne, short stories (vintage, 1955)

(we combined two months, so i didn't have 10 photos, so i included the nachos i ate when we met to discuss munro's the beggar maid.)

in 2015, i became much more brutal with dropping books because life is too short for books that simply don't hold your interest. i intentionally dropped 13 books.

- claire messud, the woman upstairs (knopf, 2013): so. boring. nothing. happens.

- cheryl strayed, tiny beautiful things (vintage, 2012): i started reading this in earnest, but then i skimmed it with a friend, and then i never went back to it. strayed’s columns are generally hit or miss for me.

- atul gawande, being mortal (metropolitan books, 2014): this wasn’t what i was expecting it to be ... though i’m also not entirely sure what i was expecting it to be. i think i was expecting more profundity, and i wasn’t taken by the writing.

- renee ahdieh, the wrath and the dawn (putnam, 2015): omg, the sheer amount of adverbs in this made me want to throttle the book. i always read with a pencil to mark passages i like or to jot down thoughts, but i read this with a pencil to cross out all the adverbs and circle all the different variations of “said” -- i want to ban her from using a thesaurus ever again. and limit how many adverbs she's allowed to use.

- rebecca mead, my life in middlemarch (crown, 2014): i really liked what i read of this, but i finished middlemarch and didn’t like that that much, so i never did finish the mead.

- rabih alameddine, an unnecessary woman (grove, 2014): i just stopped reading this -- like, i put it down for the day and kind of forgot i’d ever started reading it, which was weird because i started reading it on oyster books and liked it enough that i bought the paperback … and then i never went back to it and probably never will.

- ta-nehisi coates, between the world and me (random house, 2015): i know; i’m horrible for dropping this; but i did. i never finished reading it for book club, and i didn’t finish it after book club and have no inclination to pick it up again.

- jesse ball, a cure for suicide (pantheon, 2015): this tried too hard to be … whatever the hell it is.

- virginia woolf, mrs. dalloway (vintage, 1992): ugh. i'm sorry, michael cunningham, but UGH.

- emile zola, thêrèse raquin (penguin, 2010): given the plot, this is going to sound bizarre, but i was bored to death with this. it was so predictable.

- philip weinstein, jonathan franzen (bloomsbury, 2015): given my unabashed, vocal love for franzen, you’d think i’d be all over this, but, as it turns out -- and i say this in the most non-creepy way possible -- i know way too much about franzen’s bio already. also, my brain kept going off in all sorts of directions because it’s already full with my own critical analyses of franzen, and weinstein’s writing is very flat. one day, i'll write about franzen.

- shirley jackson, we have always lived in the castle (penguin, 2006): so. boring. nothing. happens.

- nathaniel hawthorne, short stories (vintage classics, 2011): (no comment.)

in 2015, i took a lot of photos of books with food, and i am not going to count them all. here are 5 i randomly chose so that i'd have 7 "in 2015"s instead of 6.

and that's all, folks! stay tuned for my year-end recap coming ... at some point in the next two weeks. >:3 happy new year!