there are books, and then there are books, and that isn’t meant to imply that one is better than or superior to the other. when i say books vs. books, i mean that there are books we read and move on from and there are books that impact us in one way or another. there are books we finish and shelve, and there are books we keep coming back to, carry around with us, return to time and time again. there are books that stick with us, that leave us with a sense of urgency, maybe a deeper awareness of something in the world. there are books that make our hearts race, that we immediately run into the world waving in the air and telling everyone about.

maybe to add to that, i find it disingenuous to pretend that books — that art in general — doesn’t exist within the world, that they can be (and, sometimes, ought to be) more than entertainment or escapism. books are oftentimes vehicles through which we, whether as writers or readers, try to make sense of the world, and the books that succeed in this are those that don’t moralize or directly take on a message. they’re the books that don’t forget that they are books, this is fiction, and they are here to tell stories about people and that these stories, these people, in turn, tell a greater story about the state of the world.

so, here are three books i found hugely impactful, that i would recommend. trigger warning for depression/suicide, homophobia/religion, and rape.

miriam toews, all my puny sorrows (mcsweeney's, 2015)

you can’t flagrantly march around the fronts of churches waving your arms in the air and scaring people with threats and accusations just because your family was slaughtered in russia and you were forced to run and hide in a pile of manure when you were little. what you do at the pulpit would be considered lunatic behavior on the street. you can’t go around terrorizing people and making them feel small and shitty and then call them evil when they destroy themselves. you will never walk down a street and feel a lightness come over you. you will never fly. (toews, 178)

all my puny sorrows only came into my possession because i subscribed to a month of my book hunter, an online book community where subscribers are mailed an unknown book a month. this happened to be the title chosen the month i subscribed, and i started reading it completely blind because, apparently, synopses on book flaps or on the backs of books are not things i read and retain. (i don’t know why that is; the same thing happened with janice y.k. lee’s the expatriates, though to significantly less successful results. if i’d actually paid attention to the book flap, i likely wouldn’t have picked it up — so maybe my inability to read and retain works to books’ advantage.)

i was so drawn to yoli’s voice in all my puny sorrows, though, that i kept reading even after i figured out that this was a book about two sisters — the narrator, yoli, is an “ordinary” woman, her sister, elf, a brilliant pianist who is severely depressed and suicidal. maybe it’s important to note that this is not a book i would normally read — depression and suicide are intensely personal topics to me, so much so that one of my rules is that i actively avoid books about depression and suicide, specifically those written by people who have lost people to depression/suicide. this actually has little to do with triggers and mostly to do with stigma, shame, and power, and i’ve touched on it briefly on instagram.

there was something about yoli’s voice that just kept me reading, even if i were reading with a whole lot of wariness, ready to set the book down and walk away at any moment. there was something about her, about elf, about them together, that i felt so intensely connected to, something so genuine and real and alive. toews doesn’t romanticize or glorify depression/suicide, and neither does she judge, condemn, or dismiss it but rather tackles it head-on in all its complexity and brokenness and pain. she’s not here to make nice with this novel, whether about mental illness or about the health care system or about people’s right to make end-of-life decisions, and, most importantly, she’s not here to bullshit anyone about the realities of what it’s like to love someone who’s depressed and suicidal.

maybe it’s worth explaining (if it isn’t clear already) that i have struggled with severe depression. it’s the obvious reason why i’m so invested in starting open, frank, safe dialogues about depression/suicide specifically and mental health generally, and it’s why i’m on my eighth year of working on a collection of interrelated short stories about suicide. it’s why writing this is so fucking terrifying but why i’m doing it anyway.

it’s also why i loved all my puny sorrows so intensely.

i heard our mother speaking in her calm but lethal voice outside elf’s door. she was telling the nurse that elf hadn’t seen a doctor in days. the nurse told my mom the doctor was very busy. my mom told the nurse what she had told me the night before, that elf was a human being. the nurse wasn’t janice. my mom was asking where janice was. the nurse who was not janice was telling my mom that she agreed with her, elf was a human being, but that she was also a patient in the hospital and was expected to cooperate. why? asked my mother. what does cooperation have to do with her getting well? is cooperation even a symptom of mental health or just something you need from the patients to be able to control every last damn person here with medication and browbeating? she’ll eat when she feels like eating. like you, like me, not when we’re told to eat. and if she doesn’t want to talk, so what? (toews, 208-9)

there is no answer to the question “why?”

maybe it’s more accurate to say that there is no answer that can satisfy the asker, and there is no answer that can encompass the depth of pain and fear and conviction that delivers someone to the point of suicide.

all there can be is an attempt at understanding, an attempt at sympathy where empathy cannot be accessed, an attempt at generosity of spirit. all there can be are love and acceptance, even in grief and anger and confusion. it’s a shitty answer, but that’s the best there is — that this person you loved suffered from such pain and anguish that the best thing s/he thought s/he could do is die. to that person, there is simply no other way out, no hope in sight — and, when i read all my puny sorrows, i thought, “goddamn. here is someone who gets that.”

we sat in a café called saving grace on dundas and ordered eggs. she told me that she’s been worrying about me so much, it must be awful, everything i’ve been going through, and that in her opinion ‘to die by one’s own hand’ is always a sin. always. because of the suffering it causes the survivors. i asked her what about all the people who suffer because of assholes who are alive? is it a sin for the assholes to keep on living?

okay, she said, but we’re here on this earth, and even if we didn’t choose to be, we inherit all kinds of duties, to the people who raise us and to the people who love us. i mean, everyone has personal agonies, sure, but to die by one’s own hand, ironically enough, even though it’s an act of self-annihilation, seems to me the ultimate act of vanity. it’s just so incredibly selfish.

can you please stop saying to die by one’s own hand? i asked. well, what should i say? she said.

suicide! when someone’s murdered, do you explain it as, oh, he died by the hand of another? this isn’t the freaking count of monte cristo.

i just thought it was more delicate, she said.

and also, i said, selfish? how could it be selfish? unless you’ve seen the agony first-hand you can’t really pass judgment.

okay, she said, but if your sister had been thinking of how it would affect you when she —

AFFECT ME? i said. i’m sorry. people were looking at me. listen, i said, i don’t think you understand. i don’t want to be presumptuous, but really how could you understand what another person’s suicide means? (toews, 273)

this is ending up a lot more personal than i anticipated.

chinelo okparanta, under the udala trees (hmh, 2015)

i was raised religious (conservative christian, specifically non-denominational/presbyterian), and, until last year when i had a major break with faith, religion was a huge part of my life. for years, though, over a decade now, i struggled with how to reconcile what i believed (or what i was supposed to believe) with two specific issues: abortion and same-sex marriage. was it possible to believe in god and subscribe to these religious tenets while also upholding a belief in the firm separation of church and state? was it discrimination, or was it religious conviction? what did it mean to “hate the sin but love the sinner,” and was that even possible when “acceptance” meant demanding that queer people repress or deny an essential part of themselves and cloak it in shame?

(for the record, i do believe in the firm separation of church and state, in equal rights regardless of sexuality/sexual orientation, in women’s rights to make decisions about their own bodies. i do believe it’s discrimination and bigotry. i also stand by planned parenthood. and i have zero — and i mean zero — tolerance for shaming.)

my break with faith actually had nothing to do with sexuality (that would come later), but, when i read under the udala trees, i found quite a lot of it very familiar — the homophobia, the religious shaming, the idea of “we must pray the devil out of you.” that last one in particular drives me crazy because it’s also a common church response to depression/suicidal thinking — pray harder; spend more time in the word; you feel like this because your faith is weak. it’s total fucking bullshit.

okparanta knows her religion, and she knows how it operates, how that mentality works. the novel follows ijeoma as she comes of age in civil-war nigeria, and, when she’s sent away from home to work as a servant for a schoolteacher and his wife, she falls for a girl. they’re caught by the schoolteacher, and ijeoma is taken back home where her mother begins to work on her soul. that means hours spent praying and reading the bible, which leads to a gem like this:

the father and the levite went on to bargain over a price for the damsel, and the damsel was forced to return with the levite. on their way back to his home, they passed the town of gibeah, where most of the citizens were up to no good. one of the noble townspeople, in order to protect the travelers, offered them shelter at his home. but before the night was over, the other men of the city showed up at the kind man’s door and demanded to rape the levite. the kind man pleaded with his fellow townspeople, even offering up his own daughter to be raped instead.

rather than offer up himself to the townsmen, the levite offered up the damsel to be raped. the men of the town defiled her all throughout he night before finally letting her go. when they were done, she collapsed in front of the door. in the morning the levite came out, prodding her to get up so that they could be on their way. she did not respond. annoyed, he threw her over his donkey and took her with him that way. back at home he cut her into pieces, limb by limb, which he then sent out to all the territories of israel.

[…]

“what is there not to understand?” [mama] said. “do you not see why the men offered up the women instead of the man?”

i said, “no, i don’t see why.”

after a moment i realized that i did know why. the reason was suddenly obvious to me. i said, “actually, mama, yes, i do see why. the men offered up the women because they were cowards and the worst kind of men possible. what kind of men offer up their daughters and wives to be raped in place of themselves?” (okparanta, 79-80)

the point here is not whether this is biblically accurate or not; that’s not relevant. the point here is the way people use and manipulate religion to enforce shame — and misogyny. (the two so often seem to come hand-in-hand.)

because then there’s this:

why was it that i could not love chibundu the way that i loved amina and ndidi? why was it that i could not love a man? these days, i’ve heard it said that the gender of your first love determines the gender of all your future loves. perhaps this was true for me. but back then, it was not a thing i ever heard. all i knew is that moment was that there was a real possibility of god punishing me for the nature of my love. my mind went back to the bible. because if people like mama and the grammar school teacher were right, then the bible was all the proof i needed to know that god would surely punish me. (okparanta, 228-9)

which is put in place by years of being told this:

“marriage has a shape. its shape is that of a bicycle. doesn’t matter the size or color of the bicycle. all that matters is that the bicycle is complete, that the bicycle has two wheels.

“the man is one wheel,” [mama] continued, “the woman the other. one wheel must come before the other, and the other wheel has no choice but to follow. what is certain, though, is that neither wheel is able to function fully without the other. and what use is it to exist in the world as a partially functioning human being?”

under her breath, she said, “a woman without a man is hardly a woman at all.” (okparanta, 182)

do i need to explain why this is problematic?

a few weeks ago, i was in california with family. we were driving down from oregon back to the bay area when the topic of same-sex marriage came up, and, at one point, someone said that i likely identify with the queer community because i grew up feeling so intensely Othered myself because of my weight.

body dysmorphia and body shaming (and korean-ness and rage) are things that i will explore in the future, and, in my head, i couldn’t disagree — that is one contributing factor, reductive and dismissive though the comment was. i have always been sympathetic to the Other, which, sometimes, i think is unavoidable, being a woman of color, but the thing is that the Other, that Othering, is not just a theory or an academic point of interest. it’s a very real-life thing that affects real-life people, oftentimes in very violent, very tragic ways. people are persecuted for it; people lose their lives because of it; people take their lives because of it.

that’s why i resist such [hetero]normative views like those quoted above. i can’t help but see the danger in such pervasive, rigid normativity, especially when it’s enforced by religion, especially because it leads to fear — name your phobia, your -ism — to hatred and intolerance, to repression and shame and self-loathing. because, yes, i have been there, i am there, i carry those scars, that damage — i know what normativity does, so i don’t know where else to be, if not with the Other.

under the udala trees did leave me with a sense of hope — or maybe it’s more accurate to call it a hopeless hopefulness — because ijeoma does find her way out. then, in the note at the end, okparanta writes that the president of nigeria passed a bill criminalizing same-sex relationships … in 2014. and we’re only a month away from the horrific shooting at a gay club in orlando.

and yet we have books like this by a woman of color being published by one of the big 5. we have trans actresses on big television shows with prominent presence in the media. we have sulu in star trek in a same-sex relationship. maybe they’re small things in the big picture, but they’re not nothing.

in this world we live in, they can’t be nothing.

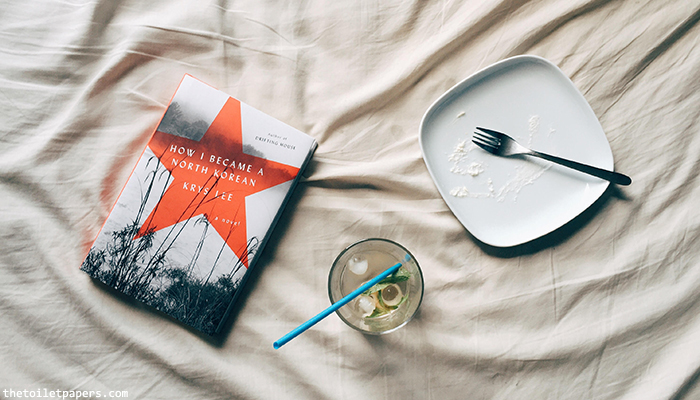

krys lee, how i became a north korean (viking, 2016)

i confess to being peeved by general media reportage or the general [western] mass attitude regarding north korea. i tend to find a lot of it sensationalistic, reductive, and dismissive — insensitive, even, forgetting that there are real human lives involved. we like to impose our “enlightened,” western perspectives on north korea, and that’s something that peeves me about how the west views the east in general, this egocentric inability to see outside the western model and this tendency to act like all cultures exist according to the same worldview — and that, if they don’t, they should. globalization does not, should not equal westernization.

what does that have to do with this novel? nothing, really.

around four years ago, i started reading about north korea. i read everything from memoirs by refugees, historical books, political studies, etcetera etcetera etcetera, and I’ve attended talks and readings by refugees, by people on the UN human rights council, journalists — i’m very invested in learning as much as i can about this country, this other half of my ethnic origin, and i’ve wondered about this curiosity about mine. is it because i’m korean? is it because i’m korean-american; is it because i’m distanced from korea that i find the narrative of a divided korea so compelling?

i don’t know what it is, but i still love the way suki kim put it in her book, without you, there is no us (crown, 2014):

the korean war lasted three years, with millions either dead or separated. it never really ended but instead paused in the 1953 armistice exactly where it began, with koreas on both sides of the 38th parallel. historians often refer to it as the “forgotten war,” but no korean considers it forgotten. theirs is not a culture of forgetting. the war is everywhere in today’s koreas.

there is, for example, the story of my father’s young female cousins, nursing students aged seventeen and eighteen, who disappeared during the war. decades later, in the 1970s, their mother, my father’s aunt, received a letter from north korea via japan, the only contact her daughters ever made with her, and from that moment on, she was summoned to the korean central intelligence agency every few months on suspicion of espionage until she finally left south korea for good and died in st. antonio, texas. the girls were never heard from again. and there was my uncle, my mother’s brother, who was just seventeen when he was abducted by north korean soldiers at the start of the war, in june 1950. he was never seen again. he might or might not have been taken to pyongyang, and it was this suspended state of not knowing that drove my mother’s mother nearly crazy, and my mother, and to some degree me, who inherited their sorrow.

stories such as these abound in south korea, and probably north korea, if its people were allowed to tell them. separation haunts the affected long after the actual incident. it is a perpetual act of violation. you know that the missing are there, just a few hours away, but you cannot see them or write to them or call them. it could be your mother trapped on the other side of the border. it could be your lover whom you will long for the rest of your life. it could be your child whom you cannot get to, although he calls out your name and cries himself to sleep every night. from seoul, pyongyang looms like a shadow, about 120 miles away, so close but impossible to touch. decades of such longing sicken a nation. the loss is remembered, and remember, like an illness, a heartbreak from which there is no healing, and you are left to wonder what happened to the life you were supposed to have together. for those of us raised by mothers and fathers who experienced such trauma firsthand, it is impossible not to continue this remembering. (kim, 11-2)

maybe that explains it, maybe it doesn’t. whatever it is, if anyone’s interested, my favorite non-fiction book about north korea is still barbara demick’s nothing to envy (spiegel & grau, 2010).

i first read krys lee in 2014, and i was blown away by her short story collection, drifting house (viking, 2012). (i wrote about it here and here.) there’s this delicious thread of unease that runs through her stories, and she’s one of few korean-american writers who is able to have one foot in korea and one foot in america, straddling that divide between korean culture and korean-american culture with ease, which isn’t an easy thing to do, mind you. i’ve been looking forward to her novel ever since and am so, so excited that it’s out.

how i became a north korean follows three narrators — two north korean refugees (yongju and jangmi) and one korean-american kid (danny). danny is sent to china to meet his mother, who is there to do missionary work, but he runs away to a border city where he meets yongju, and the three characters ultimately come together in a “home” operated by a missionary group. the missionary promises to smuggle them out of china but holds onto them until danny takes matters into his own hands — and maybe it all sounds preposterous and unrealistic, but it doesn’t either, given what we know about what north korean refugees go through, how dependent they are on strangers, how they’re exploited, held in constant fear of repatriation, treated like they aren’t even human because they lack status.

i think it’s worth noting that lee actually works with refugees, so this isn’t a novel that comes out of nowhere. it doesn’t come out of mere fascination or interest or curiosity, and it’s not one of those heavily-researched novels that read like heavily-researched novels. lee brings depth and respect and understanding to these characters and their stories, and i’m not saying that people have to have first-hand experience interacting with the people or cultures they write about — but then again, you know, maybe they should. the angry asian-american in me is sick of white people writing about asia in half-assed manners and winning prizes for it.

i often think about borders. it's hard not to. there were the guatemalans and mexicans i read about in the paper who died of dehydration while trying to cross into america. or later, the syrians fleeing war and flooding into turkey. arizona had the nerve to ban books by latino writers when only a few hundred years ago arizona was actually mexico. or the sheer existence of passports, twentieth-century creations that decide who gets to stay and leave. (lee, 60)

i’ve said this before, but how i became a north korean is a brilliant indictment of everyone — and i mean everyone — in the exploitation, abuse, and mistreatment of north koreans. it doesn’t matter whether it’s a missionary, a broker, china, a magazine, a journalist, a random citizen like you and me — we’re all guilty. we’re all guilty of simply consuming sensationalist stories, of trying to profit off the lives of refugees, of trying to profit off their stories, of using them for spiritual self-elevation, of thinking we have any right to satirize so thoughtlessly a regime that abuses its own people. we’re all complicit, and we’re all guilty.

lee delivers this indictment without moralizing, without standing on a soapbox and getting preachy. all she does is tell a story — or stories, i suppose — stories full of heart and life, stories of desperation, rage, and helplessness, and she brings you into these people’s fears and vulnerabilities and hardnesses, into all the hurt and pain they’ve learned to live with, have had to insulate themselves against. i think it’s absolutely brilliant, what she’s done, and she does it powerfully in blank, naked prose. she doesn’t judge her characters, just as she doesn’t try to make them “perfect” — she simply brings them to life on the page and asks you, please, to pay attention.

and i’m not trying to get preachy about it, either. i know it’s impossible for us to care about every single issue and human rights violation out there; i would never expect that of anyone when surviving on a day-to-day basis is struggle enough. however, like i said about art existing in the world, the truth is that we also exist in the world. our actions, our inactions, our complacencies, our conveniences, our limitations — they don’t occur in vacuums. i don’t think we should walk around carrying the burden of all the world’s ailments on our shoulders; they’re certainly not all ours to bear; but i do think it’s worth acknowledging that sometimes shit happens, shit continues to happen because, whether intentionally or not, we let it.

this is how it happened. we fled in the brokers' footsteps. we scattered into small dark spaces in the backs of buildings, trains, and buses, through the great mouth of china. our feet made fresh tracks as we weaved through mountains and made unreliable allies of the moon and the night and the stars. every shadow a soldier, a border guard, an opportunist. each body of water reminded us of the first river, the river of dreams and death, where we saw the faces of people we knew and would never know frozen beneath it. the children who had run and been caught and sent back. the pregnant women repatriated to our country and thrown in jail, forced to run a hundred laps until they aborted. the women who gave birth in the same jail and saw soldiers bash their new infants against a wall to save bullets. the countless others whose peaceful lives ended when an enemy informed on them -- ours was one small story in all the other stories. we stumbled across the jungles and deserts of southern asia, seeking safety and freedom. we would look and look. a few of us would find it. (lee, 224)

a few weeks ago, jord watches contacted me about a collaboration. they sent me this watch (from their fieldcrest line), and i’ve worn it around for almost two months now. i’m someone who wears a watch everyday and feels naked without one, and i’ve been enjoying this wood watch — it’s a unique piece that’s very light and doesn’t start feeling wet or bulkyeven in heat and humidity. find more images here, here, and here, and check them out [link here] if you’re interested!

(tl;dr disclaimer: watch was provided; review is my own.)

other miscellaneous info: the coffee is my attempt at a mint mojito iced coffee, a la philz; it’s cold brew using beans (philtered soul) from philz (purchased myself in santa monica), brewed in a hario mizudashi cold brew pot (also purchased myself two years ago, used maybe twice, and stored in a cupboard until last week when i was like, wait, i have a cold brew pot; MAYBE I SHOULD USE IT), with half-and-half and mint, muddled in my glass with the end of a rolling pin. the blue straw was stolen from blue bottle (^^), and the roll cake was baked myself because, like i mentioned in my previous post, i’m obsessed with baking asian sponge cake rolls. i’ll probably bake another one tomorrow.

i purchased the books and wrote the above wall of words and took the photos myself.

thanks for reading!