- yiyun li, dear friend from my life i write to you in your life (random house, 2017)

- julie otsuka, the buddha in the attic (anchor books, 2012)

- annabelle kim, tiger pelt (leaf-land press, 2016)

- rachel khong, goodbye, vitamin (henry holt, forthcoming, 2017)

- catherine chung, forgotten country (riverhead, 2012)

- susan choi, the foreign student (harper perennial, 2004)

- min-jin lee, pachinko (grand central publishing, 2017)

- esmé weijun wang, the border of paradise (unnamed press, 2016)

- ruth ozeki, a tale for the time being (penguin, 2013)

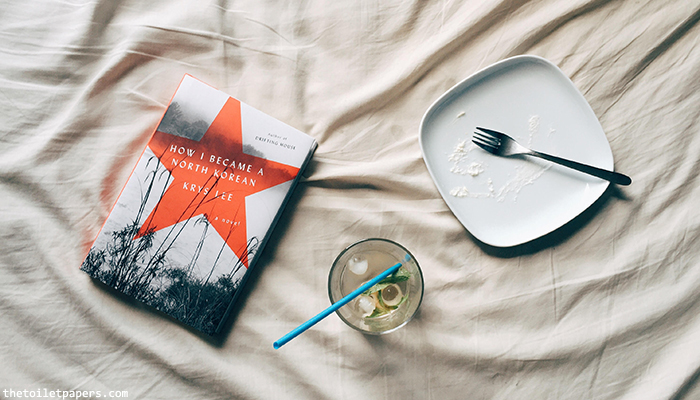

- krys lee, how i became a north korean (viking, 2016)

- celeste ng, everything i never told you (penguin press, 2014)

- jung yun, shelter (picador, 2016)

- padma lakshmi, love, loss, and what we ate (ecco, 2016)

- alexandra kleeman, you too can have a body like mine (harper, 2015)

- shawna yang ryan, green island (knopf, 2016)

it’s international women’s day, so here’s a stack that i am so fucking jazzed i can even make: i have no substantial data to back this up, but i do feel like, in the last few years, we've seen a greater rise of asian[-american] writers being published. who knows, though; maybe i've only noticed this because i've become much more intentional about who i'm reading in recent years, so maybe it’s more correct for me to say that i’m jazzed that i have a collection of books that allows me to curate such a fine stack.

(is that too self-congratulatory? but i do generally stand by my taste.)

it's international women's day, and you might be saying that this stack is so narrow in scope as to miss the point. however, i wanted to make a stack of asian-american women, so here is a stack of women writers who are either immigrants or the daughters of immigrants because the point i wanted to make is simple and universal: that we, under whichever broad ethnic umbrella people want to place and stereotype us, come from a myriad of different backgrounds, carrying so many different struggles and concerns and fears, and one of the things we, as immigrants and immigrant children, bring to this country are our stories.

to be asian-american, to be anything-american, is not to be one collective person from one collective culture. it is to be a myriad of people, to contain multitudes of women, and i wanted to create a stack that would reflect this, the international backgrounds we come from that influence, in so many different ways, the stories we are compelled to tell.

in a political climate under a toxic administration that is feeding and fostering hate against non-white, non-christian, non-straight immigrants, this is what i wanted to celebrate today — that this is a country that has welcomed people from so many places, and this, this stack here is a result of that. i want to point at this stack and say, look, look at this wealth. look at the worlds these pages contain. look at the humanity these books expose. look.

so, here is to us, all of us women, regardless of ethnicity, sexual orientation, religion, or the physical bodies we were born into. here is to the countries, the cultures, the peoples we come from. here is to the women we come from, women who have sacrificed much so we can be the women we are, women who have shown us strength and love and dedication. here is to the women who have failed us, to the women we will fail, to the women who are broken and fucked up and damaged because they are women, and to be a woman is to be human.

and here is to us. here is to the women we are and the women we are becoming and the women we will be. may we be strong and continue to tell our stories and refuse to be silenced.