ordinary, said aunt lydia, is what you are used to. this may not seem ordinary to you now, but after a time it will. it will become ordinary. (33)

hi! it’s been a whirlwind of a week-and-a-half, filled with emotions and time zones and sleepless nights. we went from los angeles to san francisco to cancún to san francisco to los angeles, and we watched my brother be wedded to my now-sister-in-law, the same weekend that i watched the hulu adaptation of margaret atwood’s the handmaid’s tale (vintage, 1985) and started rereading the novel.

which is a juxtaposition worth noting because it was a weekend of religious, church-y services, and it was a jarring juxtaposition indeed.

(there will be no spoilers for the hulu adaptation in this post. i’m waiting for the halfway point to write about that.) (all quotes in this post, except for one noted below, are from the handmaid's tale.)

it’s the usual story, the usual stories. god to adam, god to noah. be fruitful, and multiply, and replenish the earth. then comes the moldy old rachel and leah stuff we had drummed into us at the center. give me children, or else i die. am i in god’s stead, who hath withheld from thee the fruit of the womb? behold my maid bilhah. she shall bear upon my knees, that i may also have children by her. and so on and so forth. we had it read to us every breakfast, as we sat in the high school cafeteria, eating porridge with cream and brown sugar. you’re getting the best, you know, said aunt lydia. there’s a war on, things are rationed. you are spoiled girls, she twinkled, as if rebuking a kitten. naughty puss. (88-9)

if you want to spend a week feeling terror, read the handmaid’s tale and chase that with rebecca solnit’s the mother of all questions (haymarket books, 2016).

if you’re not familiar with the handmaid’s tale yet, you should be. the novel follows a first-person narrator who is named as offred, though that isn’t her actual name, simply her designation as she is the handmaid assigned to a commander named fred.

a handmaid is a class of women in this city of gilead, and handmaids are women who are still able to get pregnant and bear children, a blessing in this time when the birthrate is down and pregnancy is rare, which, of course, is a fault that is borne entirely by women because men cannot be held to blame.

gilead is a hyper-conservative, hyper-religious city, and, with her novel, atwood gives us hyper-literal interpretations of the bible. handmaids are monthly subject to “the ceremony,” in which the handmaid lays between the legs of the wife, who holds the handmaid’s wrists, while the husband fucks (read: rapes) the handmaid, a literal take of the biblical passage, genesis 30:1-3.

there’s a lot in the novel that takes the bible literally.

given that, unsurprisingly, this is a world in which women have no rights, no money, no property. instead, they are property, and it is illegal for them to read, write, think even, i dare say. it doesn’t matter whether they’re a wife or a handmaid or an aunt — and one of the things atwood does so brilliantly in her novel is to show how women are complicit in enforcing and reinforcing the patriarchy and misogyny and sexism.

gilead needs the aunts with their cattle prods and indoctrination to force the handmaids to submit. it needs the wives to call handmaids sluts and whores while requiring them for childbearing. it needs the handmaids, too, to spy on each other, report on each other, keep them in place. the patriarchy doesn’t keep itself in power simply by the participation and force of men.

and, if you think this is some far-fetched fictional world, think about this — we hold each other to impossible standards; we shame each other for dressing provocatively, wearing too much makeup, acting “inappropriately.” we blame victims of sexual assault and tell our girls that boys are being mean to them because they have crushes on them and encourage each other to stay in abusive relationships for the sake of our children. we tear each other down and keep each other in our proper place, scoffing when one of us tries to break the glass ceiling, wants more than we should, tries to be different and wants more, even if it’s something as basic as equal pay and the right to make decisions about our own bodies.

and think about this — women voted for the cheeto. women held hillary clinton to an impossible standard, despite the fact that she was qualified for the job at hand. women defended the cheeto’s horrific statement of “grab them by the pussy” by dismissing it as men’s locker talk. women voted for him. women did that.

after the wedding, my extended family — all my aunts and uncles on my father’s side — goes to mexico. it’s hard to say we go to mexico, though, because we spend the entirety of the time on a fancy resort an hour from cancún, in this little bubble enclave of wealth and pampering.

while i’m in transit, in these sleepless in-between spaces, i think about a lot of things.

i think about the bubbles these fancy resorts are, the drive from cancún international airport to the resort, this one hour traversed on a highway that crosses through trees and exposes little of the world around us. nature, here, is meant to hide. i think about the stuffy privilege of all this, of cloistering ourselves away on these all-inclusive grounds, our every need being met, greeted with smiles and friendly holas and can-i-get-anything-for-you,-miss-es? i think about the hypocrisy of being uncomfortable about all this but receiving the services, anyway, of enjoying the comforts of my privilege, of my family being one that can have.

i think about complicity, how we’re all complicit in something. i’m complicit by simply having said yes, okay, to this vacation with my extended family. i’m complicit by partaking of these services. i’m no better than anyone else just because i feel guilty — maybe i’m worse because of it — and i think, what can i do about this? what can i do instead of simply feeling badly about it?

i don’t yet have an answer to that.

i think about passports and borders and the privilege and protection my US citizenship grants me. i think about that time i was driving across the country, and i was in new mexico when all traffic was stopped at border patrol. i sat in that queue, wondering where my passport was, if i’d need it, if my california license would be enough to prove my citizenship, but, then, i got to the kiosk, and all the man asked was, are you a citizen, ma’am?

i said, yes, and he said, thank you, ma’am, and waved me through, and i thought how simple that was, how all i said was one word and that was sufficient.

on thursday, i leave cancún to return to the states, and, as i go through the airport in mexico, i think about how my US passport might be considered more valuable than my person. as i land at LAX and head to immigration, showing my passport to security who direct me to the line for US citizens, i think what a privilege this is, to be able to know that i can reenter my country of residence without trouble, that this little book of paper is enough for me to stake my claim.

i think about what krys lee wrote about borders in her novel how i became a north korean (viking, 2016):

i often think about borders. it's hard not to. there were the guatemalans and mexicans i read about in the paper who died of dehydration while trying to cross into america. or later, the syrians fleeing war and flooding into turkey. arizona had the nerve to ban books by latino writers when only a few hundred years ago arizona was actually mexico. or the sheer existence of passports, twentieth-century creations that decide who gets to stay and leave. (lee, 60)

and i think about how borders are lines on a map and passports are books of paper, and yet, and yet.

over the past week-and-a-half, i think, too, about gender treachery, about passing. passing is not something i do intentionally; i happen to be very femme; and we live in a heteronormative society that assumes straightness, especially when one fits into the expected visual of gender norms. i think about that privilege and how it’s not one i necessarily want and isn’t one i’ve pursued, but that makes me think about privilege overall and how privilege doesn’t tend to be something we’ve actively pursued — that’s why it’s privilege.

the other day, my father asked if i considered myself an activist, and i said, no, i don’t. i don’t consider myself an activist at all. just because i like to talk about things, because i believe it’s important to talk about mental health, sexuality, heteronormativity, body positivity, feminism, that doesn’t make me an activist.

what makes an activist, though? i’m loathe to align myself in such ways because i don’t think my talking about things makes much of a tangible difference. i’m not here trying to change policy or trying to advocate for more equal rights or anything; i write these words mostly in the hopes that someone out there will recognize them and maybe feel a little less alone and, in turn, will help me feel less isolated. i hardly consider that activism.

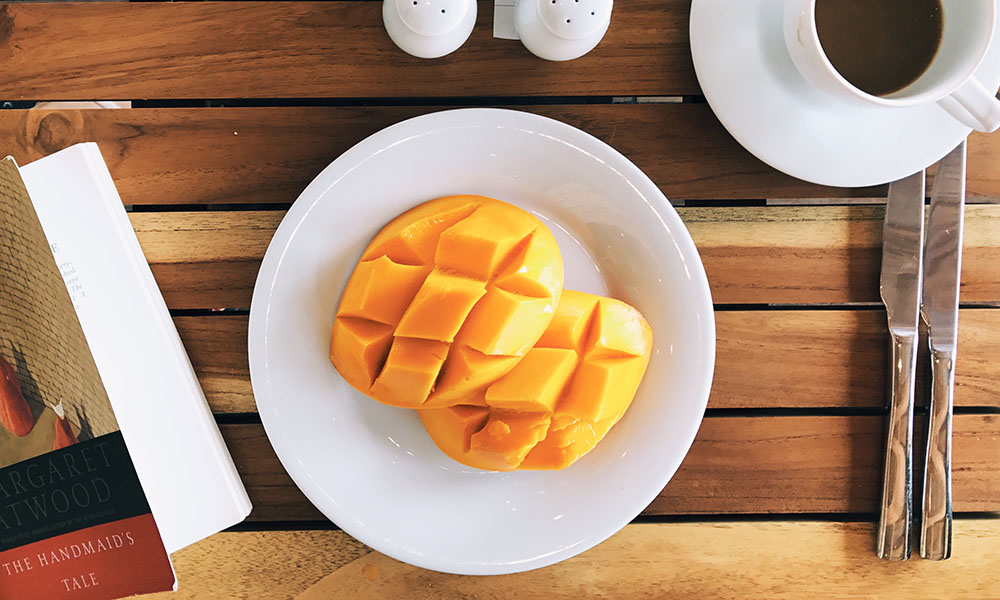

in mexico, i eat as many mango halves as i can.

the mango halves are only available during breakfast and lunch, so that means i’m eating, like, four mangoes a day because i’m eating four halves at breakfast, four halves at lunch, and i’d eat more if i didn’t think that would be overkill. maybe some people might think four mangoes a day are overkill, but i don’t — i love mangoes, though i didn’t always.

in mexico, the mangoes come sliced the way i like — cut in half, grids cut into them, the fruit still in its peel. you flip it out, so it makes for easy eating because a ripe mango will come easily off its peel as you bite into it, juice dribbling down your hands and wrists and arms. it’s sticky and messy, but it’s mango, and the mess is part of the fun.

it’s kind of like pizza; i’ll never get people who eat pizza with a fork and knife. you fold the slice in half and bring the whole thing up to your face and bite and chew and swallow. likewise, you flip the mango out, bring it to your face, and enjoy the mess it makes, just like you do with ripe, juicy peaches.

i wish i'd eaten more mangoes the two-and-a-half days i was on that fancy resort.

it was after the catastrophe, when they shot the president and machine-gunned the congress and the army declared a state of emergency. they blamed it on the islamic fanatics, at the time.

keep calm, they said on television. everything is under control.

i was stunned. everyone was, i know that. it was hard to believe. the entire government, gone like that. how did they get in, how did it happen?

that was when they suspended the constitution. they said it would be temporary. there wasn’t even any rioting in the streets. people stayed home at night, watching television, looking for some direction. there wasn’t even an enemy you could put your finger on.

[…]

things continued on in that state of suspended animation for weeks, although some things did happen. newspapers were censored and some were closed down, for security reasons they said. the roadblocks began to appear, and identipasses. everyone approved of that, since it was obvious you couldn’t be too careful. they said that new elections would be held, but that it would take some time to prepare for them. the thing to do, they said, was to continue on as usual. (174)

the handmaid’s tale reads like a warning.

do not normalize this president. do not normalize violence against women, the taking of women’s rights to make decisions about their own bodies, the denial of consent. do not normalize discrimination and hate crimes committed against people because of the color of their skin, the gender with which they identify, their sexual orientation, the god they worship. do not normalize this administration’s lies and manipulations.

do not normalize. the nightmare of the handmaid’s tale begins with normalization.

this was a travelogue.