today, when i told you to behave, you roared angrily: I’M BEING HAVE.

today, after i took my socks off, you touched my ankles — the impressions that had been left.

today you put my hand on the impression left by your sock. my hand could circle your whole miniature ankle.

today, after you lost a tooth, you cried that you looked like a pumpkin.

today i had to stop by the post office, and you looked around and said, aghast, “this is errands?”

today, while i was changing your brother’s diaper, and putting baby powder on him, you burst into tears and begged me not to put too much salt on him.

today you were so readily impressed by me. (khong, 101-2)

let's talk 2017 and books.

i started off 2017 with rachel khong’s goodbye, vitamin (henry holt, 2017), which i read mostly while i was on the road and trying to ignore the way my heart was breaking. i drove from brooklyn to los angeles in january, leaving behind my home city to return to the city in which i was raised, the city i’d been trying for so much of my life to flee, and i left brooklyn in disappointment, my tail between my legs. new york city is a tough city, even for those who love her and find solace in her streets.

goodbye, vitamin is a novel that sneaks up on you. it’s not a book that hooks you and keeps you reading maniacally; it’s a book that crawls onto you and sinks into your skin and settles in your heart. khong’s writing is warm and funny and wise, and the premise is so totally human — 30-year-old ruth returns to her parents’ home because her father has alzheimer’s. she’s recently broken up with her fiancé. she’s in this in-between.

i tend to believe that, sometimes, books find us when we need them, and goodbye, vitamin was one such book. january kicked off 2017 brutally, and i was in a horrible place, grappling with heartache, insomnia, anxiety, the worst and most prolonged bout of suicidal depression i’ve had yet. i didn’t know what the hell i was doing with my life. i felt like i’d failed at everything, unable to find a full-time job, to make enough to make ends meet, to finish my book and find an agent and sell it. needless to say, i didn’t much feel like reading.

when i drove across the country, i had a van full of books, but goodbye, vitamin was the one i carried with me. i read it during solitary meals at momofuku ccdc (DC), xiao bao biscuit (charleston), surrey’s (new orleans), solid grindz (tucson), king’s highway (palm springs), and i read it in snatches because i couldn’t focus long enough on words, on story — everything still hurt too much. it was comforting, though, tapping into bittersweet nostalgia because goodbye, vitamin, at least to me, is steeped in nostalgia. ruth, too, is returning to los angeles, to her parents’, and, at the time i was reading the novel, i was as well.

there was a lot that i personally identified with, too — my paternal grandmother passed away from alzheimer’s the summer of 2012. i didn’t live at my parents’ at the time, but i was in school an hour away, and i’d come over on the weekends to stay with her so my parents could go to church. she’s the grandmother who raised me, who doted on me, who loved me most of all her grandchildren, and she’s the reason i’m bilingual, bicultural. maybe it’s wrong to pick favorites, but she’s the grandparent who meant the most to me.

the thing with illness, as i’ve learned, is that it brings out the great in people sometimes. i’m not trying to romanticize illness at all; as someone who lives with depression and diabetes, i am not someone who would ever sentimentalize or romanticize or put a stupid silver lining on illness. at the same time, i can’t deny that the reason i have survived this year is that the people around me have shown up and shown their goodness constantly, and i am so humbled and so grateful for all the generosity, love, and understanding i’ve received.

books are part of that, too, and i believe that writing, also, is an act of generosity, and i am grateful — always grateful — for all the writers out there who write and put their stories out there, so saps like me can read them and weep and feel known. because that’s how i felt when i was reading goodbye, vitamin, and it was the perfect first book to read in what would be a tumultuous, rocky 2017.

on my way home i stop at the grocery store and buy a head of garlic and a can of tomatoes. canned goods are forbidden, of course, but i am feeling defiant, and how is mom going to find out, anyway?

mom’s thrown everything out but a glass baking dish. she claims she’s shopping for safer cookware. i spread the tomatoes on the baking dish, with salt and oil, brown sugar, slices of garlic, and ancient dried oregano from a sticky plastic shaker.

while the tomatoes are roasting, i rinse the tomato can out and boil the water in the can itself. i cook the pasta in batches in the small can. i toast the almond from the pantry and blend them with the garlic and the tomatoes and the herbs. suddenly there is pasta and there is sauce and the semblance of a real meal. i set the table for two. i head upstairs and knock on his door and call “dad?” (khong, 60)

there is no ladder out of any world; each world is rimless — my friend amy leach writes. a ladder is no longer what i am seeking. rather, i want one day to be able to say to myself: dear friend, we have waited this out. (li, 201)

2017 is the year i finally got professional help for depression and anxiety, and it’s the year i finally started seeing a therapist and taking meds.

i’ve known for years that i needed to do this, that depression was just something i was going to have to learn live with, part of which entails getting the proper help for it. i can’t quite say what it was that kept me from getting help, though, maybe a combination of insurance and shame and fear that, once i was diagnosed, that diagnosis would follow me around everywhere and i’d never find a job, never find a partner, never be more than my depression.

which is all bullshit — one of the things i’ve realized about myself when looking back at 2017 is that i’ve never let my depression stop me. even in the worst of it, i was still trying to write; i was creating content regularly for this blog; i started a full-time job and finished my book and have posted regularly and thoughtfully on instagram. there is no doubt about it; i am more than my depression.

and that’s not to make myself sound better than other people who live with depression and can’t get out of bed, can barely muster up the energy to eat something, take a shower, sit up straight. i’ve been there, too. i still have days when i’m so low-energy, i go straight home to bed and sleep ten hours. i have really shitty days when my brain fog is so bad, all i can do is have a cry in the bathroom and chug a stupid amount of coffee and chat with my coworkers until i’m powered enough to get through the rest of the day.

what meryl streep said at the 2017 golden globes has stuck with me all year, though — “take your broken heart and turn it into art.” and maybe that’s where my sense of purpose comes from, that, yes, i’ve been nursing a broken heart all year, and i’ve been worried and stressed about my broken brain, but, hey, i’m still here, and, somehow, i’ve made it through. if i can, so can you.

what does this have to do with yiyun li’s dear friend, from my life i write to you in your life (random house, 2017)? dear friend is li’s memoir about her experience living with suicidal depression, and li herself has survived two suicide attempts. this book was published at such a timely moment for me, but i don’t really want to get into it all here again, but i wrote a post dedicated to it if you’d like to check that out. the link is here.

i took rebecca solnit’s the mother of all questions (haymarket, 2017) to the bay area as a talisman of sorts the weekend of my brother’s wedding. i’m an outlier in my family in that i don’t want kids, have never wanted kids, still don’t want kids, and i like that we’re finally at a point in time where women can say they don’t want children, and, no, it’s not selfishness, it’s not self-absorption, it’s not some kind of malfunctioning on our ends. it doesn’t mean we’re defective or faulty or not fully-formed or incomplete or whatever just because we choose not to spawn.

i love the way solnit writes about all this, partly because she does it with so much more generosity than i can. she writes about womanhood, about being a woman in this world, with such intelligence and poise, and i find myself blocking off passage after passage because i’m agreeing so hard, i feel like i’m nodding my head off.

such questions [why don’t you have children?] seem to come out of the sense that there are not women, the 51 percent of the human species who are as diverse in their wants and as mysterious in their desires as the other 49 percent, only Woman, who must marry, must breed, must let men in and babies out, like some elevator for the species. at their heart these questions are not questions but assertions that we who fancy ourselves individual, charting our own courses, are wrong. brains are individual phenomena producing wildly varying products; uteruses bring forth one kind of creation. (4)

&

some people want kids but don’t have them for various private reasons, medical, emotional, financial, professional; others don’t want kids, and that’s not anyone’s business either. just because the question can be answered doesn’t mean that anyone is obliged to answer it, or that it ought to be asked. the interviewer’s question to me was indecent because it presumed that women should have children, and that a woman’s reproductive activities were naturally public business. more fundamentally, the question assumed that there was only one proper way for a woman to live. (5)

&

our humanity is made out of stories or, in the absence of words and narratives, out of imagination: that which i did not literally feel, because it happened to you and not to me, i can imagine as though it were me, or care about it though it was not me. thus we are connected, thus we are not separate. those stories can be killed into silence, and the voices that might breed empathy silenced, discredited, censored, rendered unspeakable, unbearable. discrimination is training in not identifying or empathizing with someone because they are different in some way, in believe the differences mean everything and common humanity nothing. (36)

also, LOL, it’s only when i was collecting quotes for this post that i realized that i didn’t actually finish reading this. i got halfway through and apparently was emotionally wiped.

here’s something random: i read patty yumi cottrell’s sorry to disrupt the peace (mcsweeney’s, 2017) because i saw a photo of her and was like, whaaat, she cute.

i’d been seeing the book around social media and had been intrigued by the title and cover, but i typically avoid books about people who have lost someone to suicide. theirs is not a narrative i’m interested in, much like i’m not interested in the narratives of adoptive parents — i’d rather hear from the suicidal and from those who were adopted, and that put me in a bit of a quandry because sorry to disrupt the peace is told by helen, a korean-american adoptee who learns about her adoptive brother’s death by suicide and returns to their adoptive parents’ home, assigning herself the mission to learn why he died.

and, so, it’s a book that sat in the back of my brain as something i’d pick up and flip through the next time i was in a bookstore, but, then, there was the photo thing, and, then, i was in mexico after my brother’s wedding, and, somewhere in between eating all the mangoes i could find and rereading the handmaid’s tale, i was like, omg must. find. the. cottrell. NOW.

so, once i was back stateside in SF, i visited two bookstores to find it.

and then i devoured it.

and abso-freaking-lutely loved it.

it isn’t often that i come across writers who make me think, holy shit, you’re doing something really cool with narrative and voice here, but that’s how i felt as i read sorry to disrupt the peace. helen’s narrative voice is unique and individual, and she’s a little weird (to put it one way) and kind of abrasive, though not intentionally, because she’s clueless and has no sense of self-awareness, occupying her own headspace without the ability to read other people and situations external to her.

some have read sorry to disrupt the peace and tried to diagnose helen, but i don’t know — when i read it, i didn’t get the sense that cottrell is trying to make any kind of statement about mental illness. i don’t think that was the point, which might ask the question, then what was the point? which in turn makes me ask, do books have to have a point?

because why do we read? what are we looking for when we read? do we look at authors to make statements, deliver commentary? and should we even be making armchair diagnoses, anyway, because i hate those because armchair diagnoses are often people making snap judgments about mental illness and staying within their misguided prejudices and gross stereotypes — and, omg, does it make a difference either way, whether helen is mentally ill or mentally stable? does it make her any less credible a narrator? does her experience become any less authentic and fully-lived?

and, wow, that was a tangent, but sometimes it peeves me when we get lost in these roundabout discussions about a character’s (usually a woman’s) likability or credibility or knowability, particularly when it comes to books like sorry to disrupt the peace because, holy shit, this book is phenomenal. it’s raw and dark and funny, and helen is earnest and kinda really messed up and sad and angry, and the novel will make you laugh and cry and think about what it means to be known, to know yourself, to exist in a world that is at odds with you, that doesn’t seem to have a place for you even though you try — oh, you try, but, sometimes, trying isn’t good enough.

you try, but, sometimes, the loss you carry is not just your own.

a lot of people kill themselves, i said, but it seems like most of them do it when they’re older, like after they’ve reached middle age. we try everything we can to preserve ourselves and yet eventually something catches up with us, something dreadful creeps up, and we just can’t do it anymore. then we throw our lives away, into the trash heap of suicides. (cottrell, 70)

do what you want is a zine from the UK that features writing about mental health and nothing else. i learned of it because esmé weijun wang (author of the fabulous the border of paradise [unnamed, 2016]) contributed an essay to it, and i’m glad i did — i’m all for more candid writing about mental health by people who live with mental illness.

the significant traumas in my life have passed, and yet my physiological and psychological responses to them have only begun to truly interfere with my life this year. i’m used to becoming isolated by my mental health, and by people’s reactions to it: the depression and psychosis that i live with carry a great deal of stigma. but when it comes to trauma, and discussing the symptoms and triggers of my post-traumatic responses, the isolation is unlike any i’ve ever felt. and that’s without even going into the details of the actual traumatic events that scarred me, which even the saintliest soul likely finds hard to stomach. trauma, and in particular sexual trauma, has profoundly isolating effects in western culture.

we find it difficult to talk about trauma. it is difficult to be a human and to learn about the brutality that other humans are forced to endure.

[…]

i try not to be angry when others turn away. one way of coping with this social blanket of silence is a sort of absurd humour in which i laugh and don’t expect anyone else to laugh. i did it when, in a group of writers who decided to go around the circle and share the hilarious stories of losing their virginity, i said, “i was raped.” i may have laughed, because i’d ruined the game — at least for that moment. i can’t say there wasn’t a bit of bitterness to my actions. i did it again when, in that hospital in new orleans, with my partner and a doctor leaning in to catch my every word, and pneumonia in my chest, i blurted it out — “rape” — and fell about laughing.

[…]

[…] sometimes the only way we can bear to react is by filling the silence with laughter, even if we’re laughing alone. (esmé weijun wang, “laughing about pneumonia,” 70-2)

&

however, just because medication which increases the levels of neurotransmitters in our brains can help relieve our symptoms, it doesn’t mean that all mental illness is necessarily caused by a lack of these chemicals in the first place. the onset of mental illness is more complex, and often involves an interaction of lifestyle, environmental and biological factors. to put it simply: taking paracetamol helps to relieve the symptoms of a headache, but that doesn’t mean the headache was caused by a lack of paracetamol! (becky appleton, “sweeten the pill,” 105)

&

“i feel” does not have to mean “i am.” (eleanor morgan, “plastic minds,” 145)

i have really strong emotional sentiments when it comes to bodies.

no one’s going to be surprised when i say hunger (harpers, 2017) is one doozy of a book. roxane gay writes candidly about her trauma and her body, about the ways people see her body and judge her by it. she writes about girlhood and the ways boys violently took it away, and she writes about the gang rape that led her to eat and eat and eat, to hide herself in a body no one could hurt again.

i think about bodies often; i’d say i think about bodies every day. i think about my body, about the bodies of people i see around me, and i think about how something so common to everyone is weaponized to destroy so many of us and shred any sense of self we may have. there’s little that angers me more than a woman putting a girl (or woman) down for her body, calling her fat, criticizing her looks, commenting on what she’s eating, and, all along, basically teaching her that her value and self-worth are directly tied to her body, that she is only as worthy a human as her dress size.

and don’t even get me started on men doing that shit to women.

i’m going to put this in caps because it should be: YOUR BODY DOES NOT DETERMINE YOUR SELF-WORTH. YOUR LOOKS DO NOT DETERMINE YOUR SELF-WORTH. PEOPLE WHO MAKE YOU FEEL OTHERWISE ARE SHITTY.

it doesn’t matter what has brought you to the body you inhabit. it could be trauma; it could be illness; it could be choice, the result of decisions you’ve made for whatever reason. it could be genetics, and it could be lifestyle, and it could be financial situations. it could be a whole lot of things, none of which gives anyone any right to shame you for your body.

one of the more valuable things i’ve learned over 2017 is that i can’t control how other people feel about me but i can control how i let them make me feel about myself. i can let someone make me feel like shit, like i’m stupid or ugly or unworthy to be seen because i’m not thin, or i can say, screw that. i’m fine the way i am, and i’m going to live my life. that’s power, i think, that’s where power lies, so don’t give that power to people who demean you and put you down and tear you to pieces (then have the audacity to turn around and wonder what your problem is, why you have no confidence or self-esteem or sense of identity). people will think what they do, and, yes, sometimes, they’ll think really ugly things, but you can’t control that, so don’t waste your life — the one life you have — trying to please people who will never be happy for you, for whom you will never be good enough because you’ll never be thin enough because, when people are stuck in that mentality, no size is small enough to be good enough.

celeste ng’s debut, everything i never told you (penguin press, 2014), was my favorite book of 2014, and i’m almost annoyed that it only took her three years to publish her sophomore novel. it took me nine years to write one book and god knows how long it’ll take me to get that one published, and, already, celeste ng has published two stellar, phenomenal books.

because little fires everywhere (penguin press, 2017) is just as good as her debut. it’s hard for me to summarize because i’m shitty with book summaries, but the novel is set in shaker heights, ohio, which is an actual place, the city, actually, where ng grew up. there’s a suburban family with a nosy mother who writes for the local newspaper and fancies herself an investigative journalist; there’s a single mother who moves into town with her daughter and cleans house for said suburban family. the mother doesn’t disclose much (if anything at all) about her daughter’s father, and her presence goes against everything shaker heights stands for and turns things upside down.

i love how ng writes about suburban america, and i love the way she writes about race. she writes about it by not obsessing over it, by acknowledging that race is a thing, that we do not and cannot live in a colorblind world, that people of color are more than the color of their skin.

(i hate this notion of colorblindness; when someone claims, oh, i’m colorblind; i don’t see color; i see people, my brain interprets that as, oh, i see everything through the filter of whiteness, so i think all cultures should just be white and conform to white POVs and standards and expectations and wants and boringness. my brain also interprets that as, hi, i’m totally blind to my own privilege as a white or white-passing or i-think-i’m-white person.)

i love how she does all this by writing people because i think that’s what ng does so well — write people, people who are fleshed out and alive, who exist and want and hurt. she writes with empathy. she writes people i can’t help but care about, and she also writes people i totally loathe, but, basically, the point kind of is — you don’t passively read an ng book.

i’d say i have this massive giant soft spot for jenny zhang, but that sounds gentler than it actually is because, whenever i see her book or anything she’s written, my immediate impulse is to yell, HI JENNY ILU.

i’ve written about jenny before and how i came across her (and esmé’s) writing and how it was pretty damn formative for me. i’d grown up reading just dead white people, mostly dead white men, and i don’t think i’ll ever forget that first HOLY SHIT! moment when i came across their blog, fashion for writers, and realized that, hey, there are asian-americans out there writing things and they’re writing things that are humming with life and want and grossness and displacement and everything.

sour heart (random house, 2017) reflects all this.

i’ve read the criticism that all the stories in the collection read the same, like it’s the same narrator over and over again. i can see where that’s coming from, but, for me, i kind of liked that — i thought it kind of made the point that, yes, maybe, on the surface, we might seem the same — immigrant children with our immigrant parents and our immigrant lives. maybe we might all seem to have lived the same story, but, when people manage to look beneath that, they might find that we’re different, that, much like white people with whiteness, sometimes, the only thing we have in common with each other is our asianness, our Otherness.

i loved this about being in new york, realizing that there are so many different ways of being asian-american. growing up in the valley, near LA’s koreatown, i thought there were only a handful of different kinds of koreans — fobs, ktown koreans, valley azns, banana koreans, and people like me, second-generation korean-americans who were bilingual and bicultural.

getting out of this bubble and getting out of my loathed familiar zones, out of a city of life in cars and into a city of subways and walking and public transportation, i had to reassess asian-americanness. the best thing moving to new york did for me was open up my mind and make me at least a little less judgmental and more accepting. i don’t believe there is one way to be asian-american; i believe there are as many ways to be asian-american as there are asian-americans; and i don’t subscribe to the notion of a “good” asian-american or a “bad” one. i believe we all individually negotiate our relationships with our ethnic heritages.

part of me wishes i could say i believed this when i was younger, too, but the truth is i didn’t. i was kind of a snoot about my koreanness, the fact that i could speak, read, write korean, the discomfort i felt at not feeling korean enough or american enough. i held it as a sort of pride that i walked this line between cultures, like that was some kind of accomplishment of my own, and, now, years later, at least, the thing i can be grateful for is that, as humans, we are growing and changing creatures, and we can always come back from bad places. we can be better people. we can be kinder, more generous, more open-minded. we can be more loving.

we just have to try.

… my absolute favorite thing, starting around the age of five, was watching discovery channel’s great chefs of the world. seeing alain passard make cassoulet, raymond bland creating cakes and confectionaries, and takashi yagihashi working acrobatics (purpose, no wasted movement, efficiency) with his mind-bending noodles — though i didn’t know their names then, i was mesmerized by the mix of global chefs and of places i could only dream of visiting. a great calm washed over me while watching hands work so confidently with what seemed to me then to be innate skill. seeing the chefs’ agility in the kitchen, the buzz, whisk, stir, and pour, and the little pots was very soothing to me. it was the only time in the day i’d be completely focused. after dinner i would run into our yard to create my own kitchen from twigs, stones, and dirt. i’d collect dried leaves by the handful and sprinkle them onto my tennis racket — my pan. pretending i was in whites, a little great chef, i would shake the tennis racket like i watched the great sauciers do. i imagined the sizzles and the smells.

as i got older, i stayed indoors and traded my tennis racket for an actual sauté pan, and leaves for vegetables and chicken breasts. home alone, i would throw whatever i could find into the pan and cook the shit out of everything, until it was basically sawdust. i was going through the process of cooking long before i had a concept of what went together or how to properly execute it. (kish, 10-1)

hilariously (idk why it’s hilariously, but let’s run with it), it’s thanks to instagram that i found kristen kish last year. i don’t watch top chef or follow it at all, so i had no idea who she was until she started popping up on my instagram explore page and i was like, heeeeeeeey, yer hella cute.

i was excited to learn that she was doing a book, but i was also a little apprehensive because i really didn’t want her to go down the celebrity chef route because, as hypocritical as this might sound, personal brands make me uncomfortable. i don’t like personal brands. i don’t like the falsity they conjure up.

when clarkson potter released the title and cover to her book in january, i started to get more apprehensive because everything about it was too celebrity chef-y for me. to be honest, i still don’t like the title and rarely say it (if you haven’t noticed yet), referring to it as the kish cookbook, and i’m not the biggest fan of the cover as it went to press (the one initially released was more striking and interesting, at least compared to this) (i think they should have gone with what they put under the dust jacket, though — imagine that fish done in foil, the letters pressed into the board in white — can you picture it?! that’s a striking visual that would have stood the hell out).

that said — i do see where the title comes from. kristen kish cooking (clarkson potter, 2017) is a very personal book; it’s one that goes into her history, her inspirations, her food; but it does so in ways that aren’t cloying or overly sentimental or false. the biographical introduction is brief, the headnotes to the point, and her personality comes through, not only in the recipes but also in the photographs, the plating, the design. everything is very clean and polished and refined, and i really liked that kish didn’t shy away from plating her food the way she would in a restaurant. does it look “accessible” to the average home cook? no. but does it have to? no.

the pleasant surprise has been that i have cooked a fair amount from this book and will likely continue to do so, and i am not someone who cooks from cookbooks all that often. i read a whole lot of them, yes, but i can count on one hand the number of books i’ve cooked from. as i was reading her book, though, i kept tabbing recipes that sounded curious to me, things i might like to try, and i loved each thing i made, so i kept going and will keep on going. kish’s food takes time, and it’s not very simple, but it’s well worth the time and work.

if anything, the kish cookbook has made me venture out of my comfort zones and want to try out new things, and it’s taught me that i can trust my instincts. i know generally what i’m doing in a kitchen, and i don’t need to worry about being able to feed the people i love and to feed them well. it used to a point of insecurity for me almost, and i’d feel so embarrassed about my awkward knife skills and my difficulty with seasoning, but, once i started letting go of that and being comfortable in what i can do and branching off from there — that’s really when cooking opened up for me, and this book came at a fitting time when i needed that boost and emotional support.

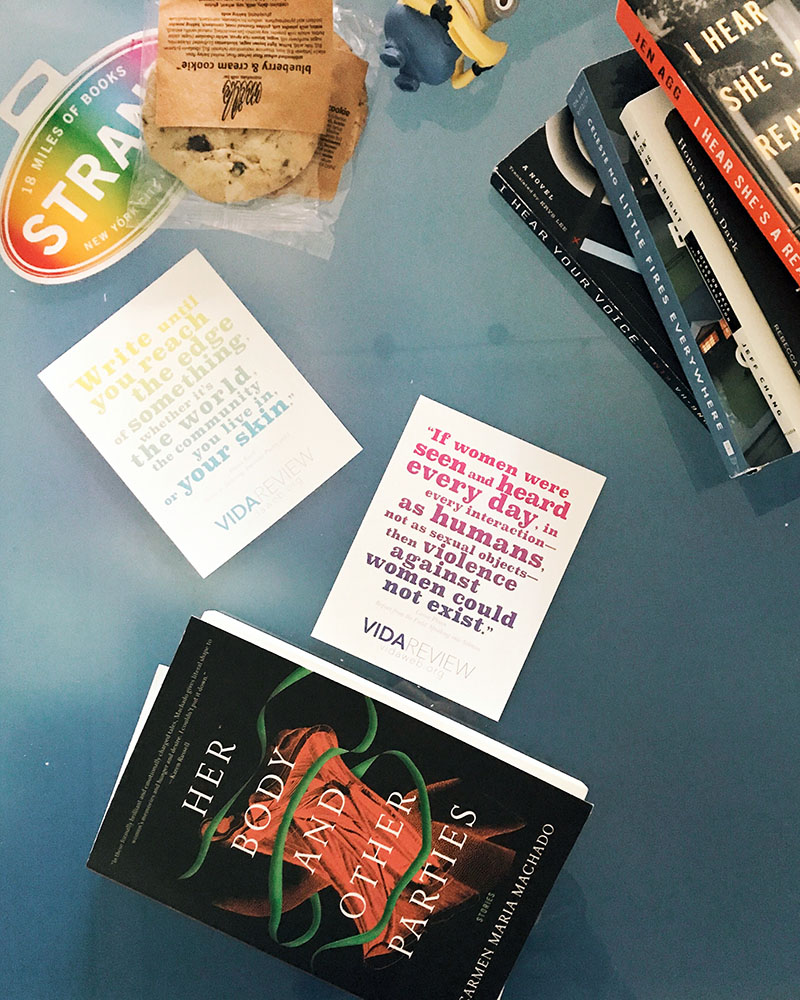

i love the way carmen maria machado writes about womanhood and queerness like they’re just totally normal parts of life — BECAUSE THEY ARE.

her body and other parties (graywolf, 2017) was kind of a strange book for me because i started off loving it intensely. like, i loved it. i loved her writing; i loved the weirdnesses; i loved how nitty-gritty and disturbing the stories could be. halfway through, though, starting with the long SVU story that should have been half the length it was, the collection started faltering. the stories had interesting ideas but didn’t quite achieve their potential, and they started feeling rushed, not quite fully-developed. i started liking the collection less and less, but the thing is, i’d started off with such an intense love for her body and other parties that, in the end, overall, i still loved the book.

i ended the year with julie buntin’s marlena (henry holt, 2017), which i’m still reading, and this, too, is a novel i’d seen around and wondered about. i admit i wasn’t initially curious because of the cover; i thought it might be a coming-of-age story; and, maybe, it really kind of is — it’s just darker and grittier and less sentimental and sweet than the cover led me to believe.

(i do judge books by their covers. i do not apologize for this.)

i heard julie buntin as part of two panels, though — the first at the brooklyn book festival with jenny zhang and the second at wordstock in portland with rachel khong and edan lepucki — and i had to read her book. buntin is smart, well-spoken, put-together, and i love how she talked about girls, the complicatedness of girls, the pain caused by addiction. in portland, she also read the opening passage from her book, and it’s one hell of an opening passage, and it’s with this that i will finally leave you. thank you, as always, for reading.

tell me what you can’t forget, and i’ll tell you who you are. i switch off my apartment light and she comes with the dark. the train’s eye widens in the tunnel and there she is on the tracks, blond hair swinging. one of our old songs starts playing and i lose myself right in the middle of the cereal aisle. sometimes, late at night, when i’m fumbling with the key outside my apartment door, my eyes meet my reflection in the hallway mirror and i see her, waiting. (buntin, 3)