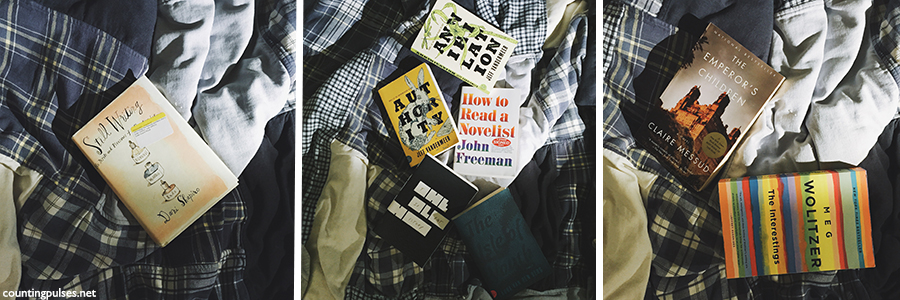

march + april! and, yes, sometimes, i read on the ipad. very, very rarely, though.

eleven. portrait of an addict as a young man, bill clegg.

his words, his caressing hand, carlos on top of me, the drugs and vodka roaring through me — shame, pleasure, care, and approval collide and the worst of the worst no longer seems so bad. one of the most horrible things i can imagine — having sex, high on drugs, in front of noah — has been reduced to something human, a pain that can be soothed, a monstrous act that can be known and forgiven. you’re okay, noah reassures me with his soft voice and gentle strokes, and for a few long minutes, i am. (133)

i read this and ninety days within 24 hours. clegg’s a pretty adept writer, and i liked how he used the third person when it came to talking his youth — it didn’t read like a shtick but created a nice sort of hazy distance between clegg the adult and clegg the child. i also appreciated that he isn’t writing to make apologies or excuses for his addiction and its consequences but simply telling his tale the way it happened, no concern for making himself look better or more sympathetic. which worked because i wasn’t very sympathetic towards him and felt myself growing frustrated and irritated with him.

this was an interesting read in that it made me step back to question how i might react if i had a friend in a similar situation. i admit that i didn’t like all the answers i discovered, but it’s refreshing when you read something that challenges you as a human being — i’d say that it really is a testament to clegg’s own stark naked honesty that i had to stop to ask myself what i would do and that the answers, in turn, challenged me to be more supportive and understanding of friends who are struggling.

twelve. ninety days, bill clegg.

so i return to new york, see the studio on 15th street, and even though the rent is pretty cheap, i can’t afford it. the landlord and broker need all that money. since jean and dave are out, and because most of my family is broke, i ask elliot. the first time in my adult life i’ve asked anyone for money, and elliot’s yes is as uncomplicated as if i’d asked him for a french fry off his dinner plate. as uncomfortable as the asking is, as grim as the circumstances are that bring me to the question, the yes is a miracle. the yes, with all its confidence and kindness, is like jane’s kiss on the street near one fifth, or jean’s bags of food. it cuts through the plaque of shame and reminds me that somewhere underneath the wretched addict is a person worth being kind to, even worth betting on. and i do not look like a good bet, that much is clear from any perspective, but when i tell elliot i don’t know when i’ll be able to pay him back, he just says, i’m not worried. i know you will. (74)

i’d say i enjoyed this more than portrait of an addict as a young man, not because ninety days depicts his struggles to get clean — i’m not really that interested in redemption stories — but because it got me in the heart with the emphasis on community. getting sober wasn’t something clegg did on his own; it was the people beside him who made the difference, whether it was by providing him with groceries or by struggling themselves to get sober or by simply waiting for him to get sober, to get back to work. there’s such a poignant beauty to that, and something convicting there, too, because it’s so easy to get wrapped up in our own worries and selfish needs, too absorbed with wanting something in return for our “generosity.” the stark naked honesty from portrait is here, too, and a whole lot of love and a whole lot of gratitude, and it really was a beautiful, humbling thing to read.

thirteen. my education, susan choi.

“come on, regina you ‘love’ me, you want to come set up house? you ‘love’ me, you want to be joachim’s other mommy? you want to pay half my mortgage? you want to bake little pies every day? what is this bullshit? what more do you want? you have me. quit the ‘gimme.’”

“what ‘gimme,’” i whispered, my throat walls grown thick.

“your ‘i love you’ is like ‘gimme, gimme,’” she said, pulling into her driveway. she turned off the engine and we listened to its tick-tick dying noise as if marking the hours before dawn. then she seized my hand and at her touch i yanked her close, a tug-of-war stalemate across the gearshift of the saab. “i want you here, too,” she whispered. “i want you sleeping with me, in my bed. i want that even though it’s insane, and my life goes to pieces if we get ourselves caught, i still want it. can’t that be enough?” (95)

my feelings re: my education are … not smple: i found the narrator, regina, both fascinating and irritating (she cries a lot), and i wasn’t necessarily that sucked into the story, but i enjoyed the book overall. it made me want to read more susan choi (i promptly went out and bought the foreign student and american woman) because i ended up really liking/enjoying regina’s voice in my education, even if i were ambivalent about her (again, too much crying). i found her arc immensely satisfying, though, loved the way she grew up and matured, and i actually liked the big time jump in my education — i think it served the story well, and i’m not really a fan of big time jumps in general because i tend to find them lazy, whether in novels or in korean dramas.

i felt pretty ambivalent about my education while i was reading it, kind of thought the story was a little whatever, but the further i got into it, the more i didn’t want to stop — the more i liked that there wasn’t a high concept or complicated narrative. i’ve also heard susan choi in conversation twice in the last few months, and i came away from both events being more curious about her and wanting to hear more from her, although she was really more the moderator at both, because she’s very smart and very poised and has an awesome haircut, which never hurts. it’s always a plus when you like the author, i say, and susan choi’s definitely on my radar now — i’ll be keeping an eye out for any other events/readings she does in nyc!

fourteen. the interestings, meg wolitzer.

but when she looked over at ash and ethan, she often felt a small reminder of how she herself didn’t entirely change. her envy was no longer in bloom; the lifting of dennis’s depression had lessened it. but it was still there, only closed-budded now, inactive. because she was less inhabited by it, she tried to understand it, and she read something online about the difference between jealousy and envy. jealousy was essentially “i want what you have,” while envy was “i want what you have, but i also want to take it away so you can’t have it.” sometimes in the past she’d wished that ash and ethan’s bounty had simply been taken away from them, and then everything would have been even, everything would have been in balance. but jules didn’t fantasize about that now. nothing was terrible, everything was manageable, and sometimes even better than that. (363)

you know, it really says a lot about a book if, as you’re flipping through it for passages you pencilled, you want to sit down and read it again. even though you’ve just read it again for a second time in less than twelve months.

i still love ethan figman.

the paperback launch for the interestings was held at powerhouse, and meg wolitzer appeared with susan choi, and it was fun listening to wolitzer talk about the book — how she, too, had been in love with ethan figman, so much so that he wasn’t flawed, that she wrote the book in order, that she tries to get to know her characters first. she also likes to read something great while writing, not really into the fear of being derivative, and thinks that flashbacks and flash-forwards are false constructs because we’re constantly toggling the past, present, and future in our lives — and there was more, but that’s all i feel like typing up here now.

i wrote about the interestings more in my 2013 reading recap, which you can read here.

fifteen. drifting house, krys lee.

he says, “appa, i can read now.”

he can read, and you were not there to teach him. (“the salaryman,” 108)

READ. THIS. seriously. read it. it’s fucking incredible, easily one of the best books i’ve read this year.

there’s a thread that runs through this collection, not necessarily a narrative or thematic thread but an emotional, atmosphere one — it starts with the first story, and, as you continue reading and getting further into the book, the thread pulls tighter, pulling you in tighter and upping the unease that’s been hovering around you as you’ve been reading. it’s a great unease fed by lee’s atmospheric prose — don’t be deceived by its seeming simplicity — and her stories are narrow in scope but so profoundly deep emotionally.

one of the things i absolutely loved about drifting house, though, is that lee has one foot firmly in korea and one foot firmly in america. i mentioned that briefly before, but that’s actually a very difficult line to straddle, i’ve found — usually korean-american authors tend to skew more american, which, but lee manages to depict both cultures in language that captures both korean and english, not only in diction but also in tone and voice. and she does it all with such finesse and ease — there’s nothing clunky about drifting house.

i know this might sound a little weird, but it’s late, so forgive me . basically, you should read it because it’s a great, incredible, unique book with a great voice, and i am so stoked for her novel, whenever it’s released!

sixteen. the corrections, jonathan franzen.

he was remembering the nights he’d sat upstairs with one or both of his boys or with his girl in the crook of his arm, their damp bath-smelling heads hard against his ribs as he read aloud to them from black beauty or the chronicles of narnia. how his voice alone, its palpable resonance, had made them drowsy. these were evenings, and there were hundreds of them, maybe thousands, when nothing traumatic enough to leave a scar had befallen the nuclear unit. evenings of plain vanilla closeness in his black leather chair; sweet evenings of doubt between the nights of bleak certainty. they came to him now, these forgotten counterexamples, because in the end, when you were falling into water, there was no solid thing to reach for but your children. (335-6)

this was a second read, too — i first read the corrections back in 2011 — and i’d say i enjoyed it just as much as i did the first time around. i still dislike most of the characters (caroline’s the worst; denise is my favourite; and i have a soft spot for alfred), but i have to give it to franzen for writing these full, human characters in a full, lived-in world — ugh, he’s so good, and what i [almost] resent him most is that he makes it read so easy. the effort isn’t there on the page, letting itself be known; the words flow easily, naturally off the page; and his dialogue is pretty damn great, too.

the thing with the corrections is that you put up with these unlikable characters for 400-, 500-some pages, but the payoff is great when the lambert children finally put their shit together and grow the fuck up and become adults. there’s a nice redemption there, and it’s not the sort that feels excessively tidy, like franzen is trying to make up for the book by sweeping up the end, but it’s a human redemption, the way that, sometimes, it really is one event that makes us sit up straight and pay attention and take responsibility for ourselves, our families, our lives — and, seriously, it’s pretty damn gratifying.

seventeen. sleepwalking, meg wolitzer.

it was children who did it, who drained the life from you, who made you run around the room playing piggyback until you were out of breath. it was children who scared you as no other people could. the first time lucy had tried to kill herself and ray had been called ashore by the local coast guard, he had seen helen standing all alone on the dock, clutching herself tightly, and he had known without any doubt that it was about lucy. he had been able to tell from the urgency of the way helen stood, and when he got off the boat he had slipped into her arms and wanted to stay there forever. (128)

sleepwalking is wolitzer’s debut novel, published when she was twenty-two, and it was reissued recently with a new cover that uses the same type that her other books use. first novels are interesting to me (franzen’s first is bizarre, but that might be because i had such a strange experience reading it) because it’s interesting to see where writers begin and how they grow, and you could definitely see the youth in sleepwalking, though you could also see the potential and how wolitzer would go on to write the interestings.

to be quite honest, i found sleepwalking pretty mediocre, nothing that spectacular or interesting. i kept wanting more to happen, but nothing really did, so it was a rather anticlimactic read.

eighteen. freedom, jonathan franzen.

she has embarrassingly inquired, of her children, whether there’s a woman in his life, and has rejoiced at hearing no. not because she doesn’t want him to be happy, not because she has any right or even much inclination to be jealous anymore, but because it means there’s some shadow of a chance that he still thinks, as she does more than ever, that they were not just the worst thing that ever happened to each other, they were also the best thing. (569)

this was a second read, too — i also read freedom back in 2011 — and i liked it a lot more this time around. my vague memory of freedom the first time around was that there was too much politicizing, too much of franzen ranting about his own sociopolitical views, but i didn’t find it to be so excessive this time around, although i did still think some of it could have been edited down. not so much to interfere with my enjoyment of it, though — i basically spent a weekend ploughing through freedom because i didn’t want to stop.

my favourite arc in freedom is that of patty and walter’s marriage. i think both characters do some terrible things to each other, but they learn from their terrible mistakes and find their ways back to each other, in a sense redeeming each other. i do think the death in freedom was a cop-out — it was too convenient, too easy — and i’m still not sold on whether or not it was necessary (or effective) to have a third of the novel be written in “patty’s” voice, but i wasn’t that bothered by it during either of my reads. i derived much enjoyment from joey’s plights, though — they were funny only because joey’s young and does grow up and learn from his stupidity — and, generally, if you were to ask me what freedom’s all about, i’d probably say that it’s a book about redemption, about these characters doing all these shitty things to themselves and to each other but redeeming themselves and each other, and it’s all pretty damn satisfying.

and you know, something franzen just does so well — he sets a general stage, introduces the characters, and then he pulls these long threads from that, zeroing in one character and then another and then another, and you’re kind of wondering how these all come together, but then he does it, weaves all the threads together, and creates this whole, complete narrative. it’s fucking great to read and a whole lot of fun.

i love franzen. i enjoy his nonfiction voice, his sense of humor, his perceptions and self-examination, his awareness, and rereading the corrections and freedom made me realize how much i love and miss his fiction voice. does he deserve all the crazy hype he gets? i don’t know; i can’t say; but is he good? hell yes, and i’d even go so far as to say that he’s better than most, at least in creating these big, expansive, human worlds with real human people — and, hey, it’s been four years since freedom, so that makes it five more years to go until we get a new novel from him?

nineteen. tongue, jo kyung-ran.

the thousands of taste buds on my tongue wake up one after the other. taste is the most pleasurable of all human senses. the happiness you get from eating can fill the absence of other pleasures. there’s a time when all you can do is eat. when eating is the only way you can prove that you’re still alive. large raindrops splatter onto the table, signaling the imminent arrival of a squall.

to eat or not to eat. to love or not to love. that is the question for the five senses. (108)

this took me a while to get through. i found it interesting because it’s about food and there are some great passages about food in it, but i also found it a little slow because the narrator seemed stuck in the same place for the majority of the book — and, when she did get into action to seek out revenge, it was abrupt, like she’d jumped suddenly from point a to point e. i could see what jo was doing by laying a gradual groundwork, but, even so, maybe it was too subtle, maybe it felt too much like groundwork without enough structure, because i would’ve loved if the narrative had built more and led more gracefully into the ending.

the ending was fantastic, though, and it was still an interesting read, and i did ultimately enjoy it, although i guess we’ll see how memorable it was.

—

currently, halfway through the emperor’s children and american woman and started the lullaby of polish girls. i don’t have any kind of “theme” as far as reading goes at the moment, just that i’m still aggressively avoiding books written in the first person and constantly looking for books that are beautifully written — and, okay, this is long enough, and i need to sleep, so good night!